|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 28(1); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

The annual incidence of skin cancer has been increasing, and surgical ablation is presently the treatment of choice for skin cancer. However, it leaves soft tissue defects that require reconstruction. The methods for reconstruction include locoregional flaps (LRFs) and full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs). We compared these two surgical methods for reconstruction of defects in the nose, which is prominently visible and the most common site of facial skin cancer, and assessed the cosmetic results by evaluating the scars.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted between July 2012 and January 2021. Patients were evaluated for scars after at least 6 months of follow-up. Patients were divided into LRF and FTSG groups. The scars were evaluated using the Vancouver Scar Scale.

Results

In total, 27 patients were included in this study. Their mean age was 66.8 years. Eighteen patients underwent LRF, and nine patients underwent FTSG. The average defect size was 1.55 cm2 in the LRF group, and 1.38 cm2 in the FTSG group. The average scar score was 1.44 points in the LRF group and 3.67 points in the FTSG group. The LRF group showed significantly lower total scores than the FTSG group.

The incidence of skin cancer has exhibited annual increases [1]. Skin cancer can be divided into the categories of malignant melanoma and nonmelanoma. In Korea, malignant melanomas account for approximately 10% of all skin cancers, whereas 90% of skin cancers are nonmelanoma skin cancers. The number of nonmelanoma skin cancer patients in 2018 was 24,511, reflecting a sharp increase from 10,007 in 2008 and 16,420 in 2013 [2]. Basal cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 50% of all skin cancers, and squamous cell carcinoma accounts for most of the remaining nonmelanoma skin cancers [3]. Skin cancer is most common in the face and neck, which are chronically sun-exposed sites, and the nose is the most frequent site of cancer occurrence in this area [4,5].

Surgical and nonsurgical treatments are available for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Nonsurgical treatments include cryosurgery, radiation therapy, topical therapy, and laser therapy. However, the treatment of choice is surgical ablation. Surgical ablation has the advantage of minimizing the recurrence rate; however, it also has the disadvantage of leaving extensive soft tissue defects, requiring reconstructive surgery [6,7].

The methods of reconstruction of soft tissue defects include primary closure, locoregional flaps (LRFs), and skin grafting. Each surgical method has clear advantages and disadvantages. Primary closure is the most commonly selected method for reconstruction because of its simplicity, fewer suture lines, and fewer complications. However, it is difficult to perform on the skin over the lower third of the nose or on skin with a large defect because of limited mobility [8]. Several studies have been conducted to determine how to effectively reconstruct soft tissue defects after cancer ablation to achieve functionally and aesthetically satisfactory results. However, it remains to be conclusively established whether LRFs or skin grafts are preferable, although conventional thought suggests that LRFs are superior to skin grafts [9-12].

In this study, LRFs and full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs) were performed for the reconstruction of nasal soft tissue defects. We designed this study to classify patients who underwent reconstruction for soft tissue defects after surgical ablation for skin cancer in the nose according to the reconstruction method used. We compared the cosmetic superiority between the two surgical methods (LRFs and FTSGs) by evaluating scars in the course of long-term follow-up.

This retrospective study was conducted from July 2012 to January 2021 in patients who underwent reconstructive surgery after surgical ablation for skin cancer in the nasal area. Only those who underwent reconstruction using the LRF or FTSG methods were included, and there were no cases of split-thickness skin grafts. All reconstructions were performed immediately after ablation, with safe margins ensured through frozen section analysis. Patients with metastatic skin cancer or complications were excluded from the study. In total, 27 patients were included in this study. Data and photographs were collected from patients’ medical records.

Patients’ scars were evaluated after at least 6 months of follow-up via their photographs. The patients were divided into two groups: the group reconstructed via LRFs and the group reconstructed via FTSGs. The scars were evaluated using the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) based on the most recent available data.

The characteristics of patients, scores for each item, and total VSS scores were compared between the LRF and FTSG groups. Scores were analyzed using the independent t-test. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P-value of < 0.05. The analysis was performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Twenty-seven patients were included in the study, of whom 12 were male and 15 were female. The mean age of the patients was 66.8 years. There were four cases of squamous cell carcinoma and 23 cases of basal cell carcinoma. The average defect size was 1.55 cm2 in the LRF group and 1.38 cm2 in the FTSG group (Table 1). Eighteen patients underwent LRFs, and nine patients underwent FTSGs. Bilobed and island flaps were the most common LRF methods. Figs. 1 and 2 show two cases reconstructed using LRFs, and Figs. 3 and 4 show two cases reconstructed using FTSGs.

The island flaps were based on the supratrochlear artery in one case and the angular artery in the other seven cases, and no additional treatment (such as debulking) was required. In this study, four flap methods were used to reconstruct the defect of the nose: the island flap, Limberg flap, bilobed flap, and V-Y advancement flap. The cases reconstructed using island flaps had, on average, the largest defects, while the other three flap methods were performed only for small defects (less than 1 cm2) (Table 2).

The LRF group scored 0.44 points for vascularity, 0.28 points for pigmentation, 0.39 points for pliability, and 0.33 points for height. The FTSG group scored 0.44 points for vascularity, 0.89 points for pigmentation, 1.22 points for pliability, and 1.11 points for height. The average scar score was 1.44 points in the LRF group and 3.67 points in the FTSG group. The LRF group showed significantly lower total scores than the FTSG group as determined using the independent t-test (Table 3).

The nose is the most frequent site on the face for the occurrence of skin cancer. Scars at this site pose a substantial challenge for surgeons because they are located in the center of the face and issues with symmetry and prominence must therefore be considered. We reviewed two methods of reconstructing soft tissue defects that occur after skin cancer ablation in the nasal area from an aesthetic point of view.

A major advantage of LRFs is that they can use the blood supply, texture, and color of the surrounding skin. However, the surgical method is difficult, and additional incision and monitoring of the flap are required. When flap necrosis occurs, the sequelae are serious, and even if successful engraftment occurs, a disadvantage of this method is that it can leave a permanent deformation of the surrounding structures. In particular, pulling of the surrounding skin due to an inappropriate design or excessive tension can cause poor cosmetic results by not only deforming contours, but also changing the positions of major facial landmarks and causing asymmetry. For this reason, it is important to be cautious when performing an LRF involving the nose and surrounding skin, which are particularly difficult to move and deform.

When selecting a flap, the location and size of the defect, the location of donor site, skin laxity, relaxed skin tension lines, and aesthetic border must be considered [13]. In this study, four flap methods were used to reconstruct defects in the nose. The average size of the defects was largest for cases of island flaps (Table 2). Although a sufficiently large flap can also be created if a transposition flap or advancement flap is used, a disadvantage of those methods is that the blood supply to the flap is uncertain [14,15].

Unlike LRFs, FTSGs do not cause deformation of the surrounding skin, do not apply tension, and have the advantage of being flexibly performed in any patient regardless of the area or shape of the defect. However, there is a possibility of scar contracture and pigmentation, and when the skin of the donor site has different characteristics from the skin of the recipient site, there is a large difference in texture, color, height, and flexibility. As such, LRFs and FTSGs have clear advantages and disadvantages, which relate not only to the primary purpose of reconstruction of the soft tissue defect, but also to the different cosmetic results of the two methods.

We found three studies comparing LRFs and FTSGs for soft tissue defects in the nose. One study conducted in Korea reported that LRFs showed much better results than FTSGs in terms of patients’ subjective satisfaction through a telephone survey [9]. Another study conducted in the United States reported that there was no significant difference in aesthetic results between the two surgical methods using visual analogue scale scores [10], and a third study reported that aesthetic deficits (bulkiness, color mismatch, atrophy) were more common in LRFs than in FTSGs [12].

Surgical ablation is generally recommended for the treatment of skin cancer, and direct closure, LRFs, and FTSGs are representative methods for the reconstruction of soft tissue defects that occur after ablation. For a defect where direct closure is difficult to achieve, surgeons have the option to perform reconstruction using either an LRF or an FTSG. When deciding which method to use to reconstruct the defect, it is necessary to consider not only the cosmetic results after recovery, but also the patient’s age and interest in his or her appearance, general condition, the location and size of the cancer, and pathological characteristics.

In this study, LRFs showed a statistically significant advantage over FTSGs in observer-rated scar scoring. However, the study had some limitations: the number of patient cases was small, the subjective satisfaction of patients was not evaluated, the location of the cancer and the size of the defect were not individually considered and analyzed, and deformities of the surrounding tissues were not considered when evaluating the scars using the VSS. In addition to this, we believe that sex, race, and location of the donor site can be considered as additional variables that might influence the evaluation of the subjective satisfaction of the patient; obtaining such clinical information is vital for the reconstruction of soft tissue defects in the facial region at and around the nose.

In conclusion, although both LRFs and FTSGs are useful as reconstruction methods for soft tissue defects in the nose, this study showed that LRFs were superior to FTSGs with regard to aesthetic results.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Youngwoong Choi is an editorial board member of the journal but was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital (IRB No. 2021-12-007) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of their images.

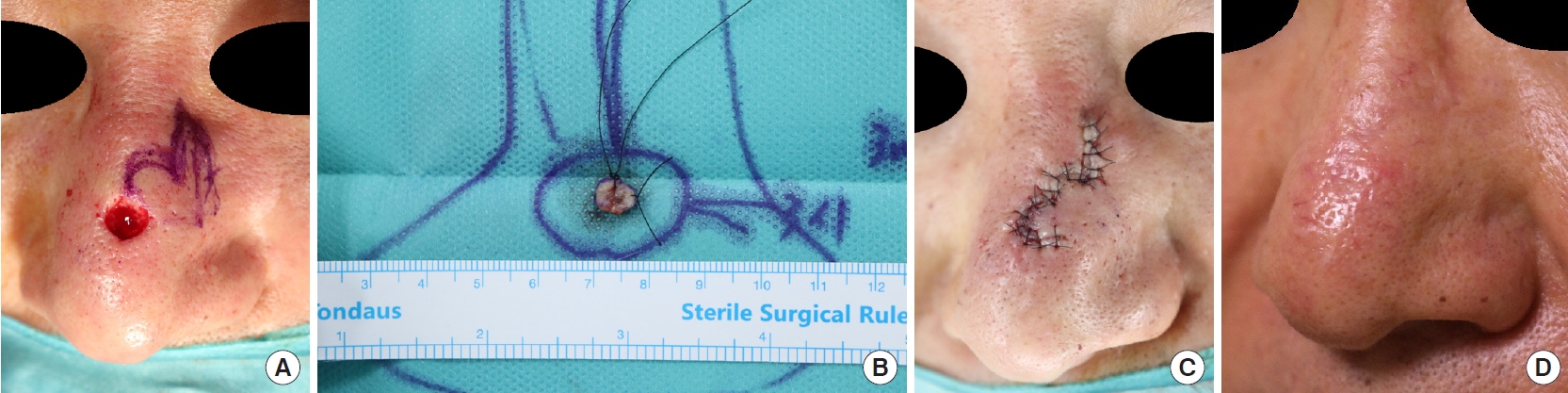

Fig. 1.

Bilobed flap for the reconstruction of a defect after surgical ablation of basal cell carcinoma in the nasal dorsum. (A-C) Intraoperatively, the defect size was 0.49 cm2. (D) Postoperative 6 months.

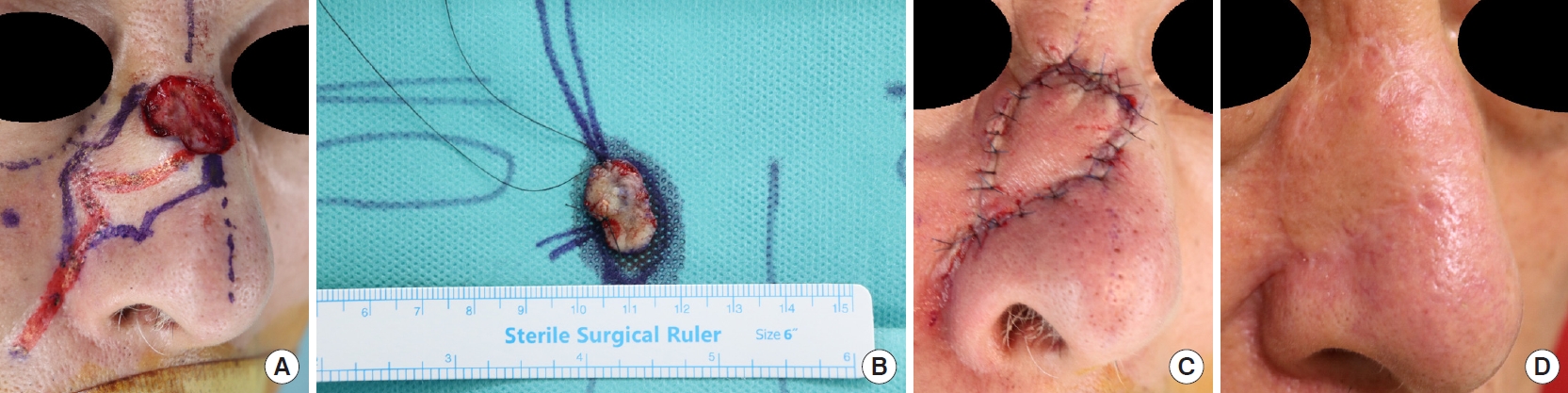

Fig. 2.

Island flap for the reconstruction of a defect after surgical ablation of squamous cell carcinoma in the nasal dorsum. (A-C) Intraoperatively, the defect size was 2.6 cm2. The flap was based on the angular artery. (D) Postoperative 6 months.

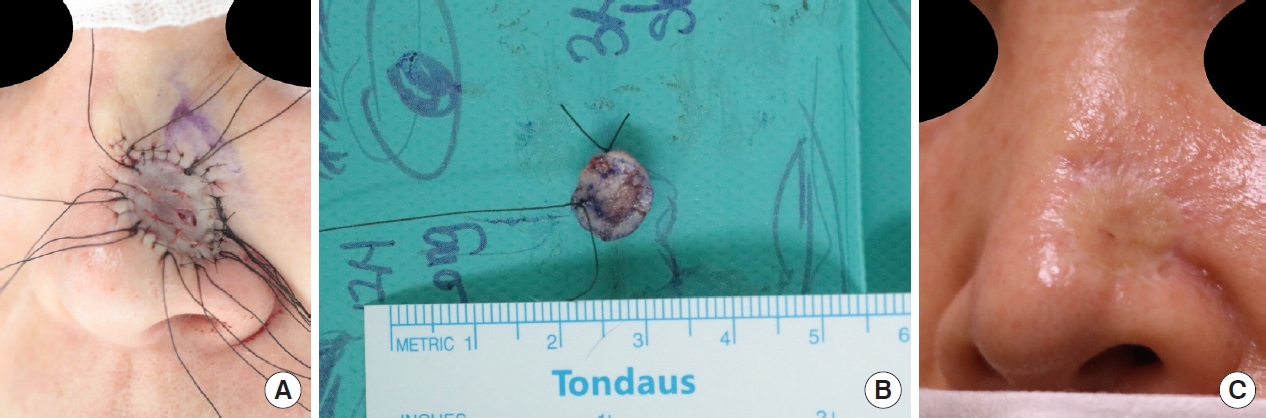

Fig. 3.

Full-thickness skin graft for the reconstruction of a defect after surgical ablation of basal cell carcinoma in the nasal sidewall. (A, B) Intraoperatively, the defect size was 1.5 cm2. (C) Postoperative 1 year.

Fig. 4.

Full-thickness skin graft for the reconstruction of a defect after surgical ablation of basal cell carcinoma in the nasal ala. (A, B) Intraoperatively, the defect size was 1.0 cm2. (C) Postoperative 2 years.

Table 1.

Patient demographics in the LRF and FTSG groups

Table 2.

Size and location of defects according to the surgical method

REFERENCES

2. Korean Statistical Information Service. Cancer registration statistics in Korea [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; c2018 [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=117&tblId=DT_117N_A00121&conn_path=I2

3. Kim SY, Kim JS, Park K, et al. Epidermal and adnexal nevi and tumors. In: Kim SY, Kim JS, Park K, et al., editors. Textbook of dermatology. 6th ed. Seoul: Daehaneohak Publishing Co.; 2014. p. 786-7.

4. Youl PH, Janda M, Aitken JF, et al. Body-site distribution of skin cancer, pre-malignant and common benign pigmented lesions excised in general practice. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:35-43.

5. Choi JH, Kim YJ, Kim H, et al. Distribution of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma by facial esthetic unit. Arch Plast Surg 2013;40:387-91.

6. Work Group; Invited Reviewers; Kim JYS, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:560-78.

7. Work Group; Invited Reviewers; Kim JYS, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:540-59.

8. Salgarelli AC, Bellini P, Multinu A, et al. Reconstruction of nasal skin cancer defects with local flaps. J Skin Cancer 2011;2011:181093.

9. Lee KS, Kim JO, Kim NG, et al. A comparison of the local flap and skin graft by location of face in reconstruction after resection of facial skin cancer. Arch Craniofac Surg 2017;18:255-60.

10. Sapthavee A, Munaretto N, Toriumi DM. Skin grafts vs local flaps for reconstruction of nasal defects: a retrospective cohort study. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 2015;17:270-3.

11. Ebrahimi A, Ashayeri M, Rasouli HR. Comparison of local flaps and skin grafts to repair cheek skin defects. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2015;8:92-6.

12. Rustemeyer J, Gunther L, Bremerich A. Complications after nasal skin repair with local flaps and full-thickness skin grafts and implications of patients’ contentment. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;13:15-9.

13. Baker SR. Local flaps in facial reconstruction. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

14. Korean Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. Paju: Koonja; 2014.