|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 27(1); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Reduction mammoplasty is a popular operation worldwide. Early complications include bleeding, wound dehiscence, and nipple-areolar complex (NAC) ischemia. Although uncommon, NAC ischemia can lead to necrosis of the NAC. NAC congestion is usually recognized intraoperatively or within a few hours of the operation. A 21-year-old woman with severe macromastia received bilateral reduction mammoplasty using a Wise-pattern reduction with a superomedial pedicle. NAC congestion of the left breast was identified 40 hours after the operation. Delayed venous congestion of the NAC after reduction mammoplasty has not been previously reported; in this case, delayed congestion may have been caused by partial venous obstruction aggravated by the progression of tissue edema near the pedicle. Through use of the delayed suture technique, application of nitroglycerin cream, intravenous administration of prostaglandin E1, and use of a portable negative-pressure wound therapy device, the patientŌĆÖs NAC was salvaged with satisfactory nipple projection and minimal scarring.

Reduction mammoplasty is a widely performed operation with excellent patient satisfaction [1]. The early complications of reduction mammoplasty include bleeding, infection, and wound dehiscence [2]. One of the most devastating complications is tissue necrosis, especially of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC). Although uncommon, NAC ischemia can lead to partial or total necrosis of the NAC [3]. Edema, blue discoloration, and dark sanguineous bleeding upon pinprick are suggestive of venous congestion of the NAC [4]. In most cases, NAC congestion is recognized intraoperatively after inset of the pedicle and the NAC or within a few hours after the completion of the operation [3,5]. Here, we present a case of delayed venous congestion of the NAC identified 48 hours after the completion of bilateral reduction mammoplasty.

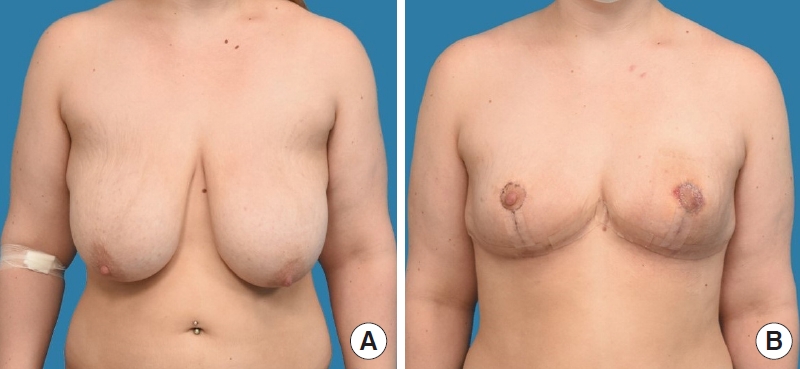

A 21-year-old woman with severe macromastia (grade III, modified Regnault ptosis scale) visited the clinic. She did not have any underlying medical conditions and reported that she did not smoke. However, she was obese, with body mass index (BMI) of 30.7 kg/m2. The preoperative assessment showed sternum-to-nipple distances of 35 cm and 36 cm, nipple-to-inframammary fold distances of 16 cm and 15 cm, and breast widths of 14 cm and 13.5 cm on the right and left sides, respectively. Bilateral reduction mammoplasty using a Wise-pattern reduction with a superomedial dermal pedicle was performed without any intraoperative incident (Fig. 1). In total, 634 g and 628 g of tissue was removed from the right and left breasts, respectively. The nipple was elevated by 16ŌĆō17 cm on both sides; the pedicle length and width were 21 cm and 8 cm, respectively, with a length-to-width ratio of 2.6:1 (Fig. 1). After inset of the NACs and upon completion of the operation, the viability of both NACs was satisfactory, without any discoloration (Fig. 2).

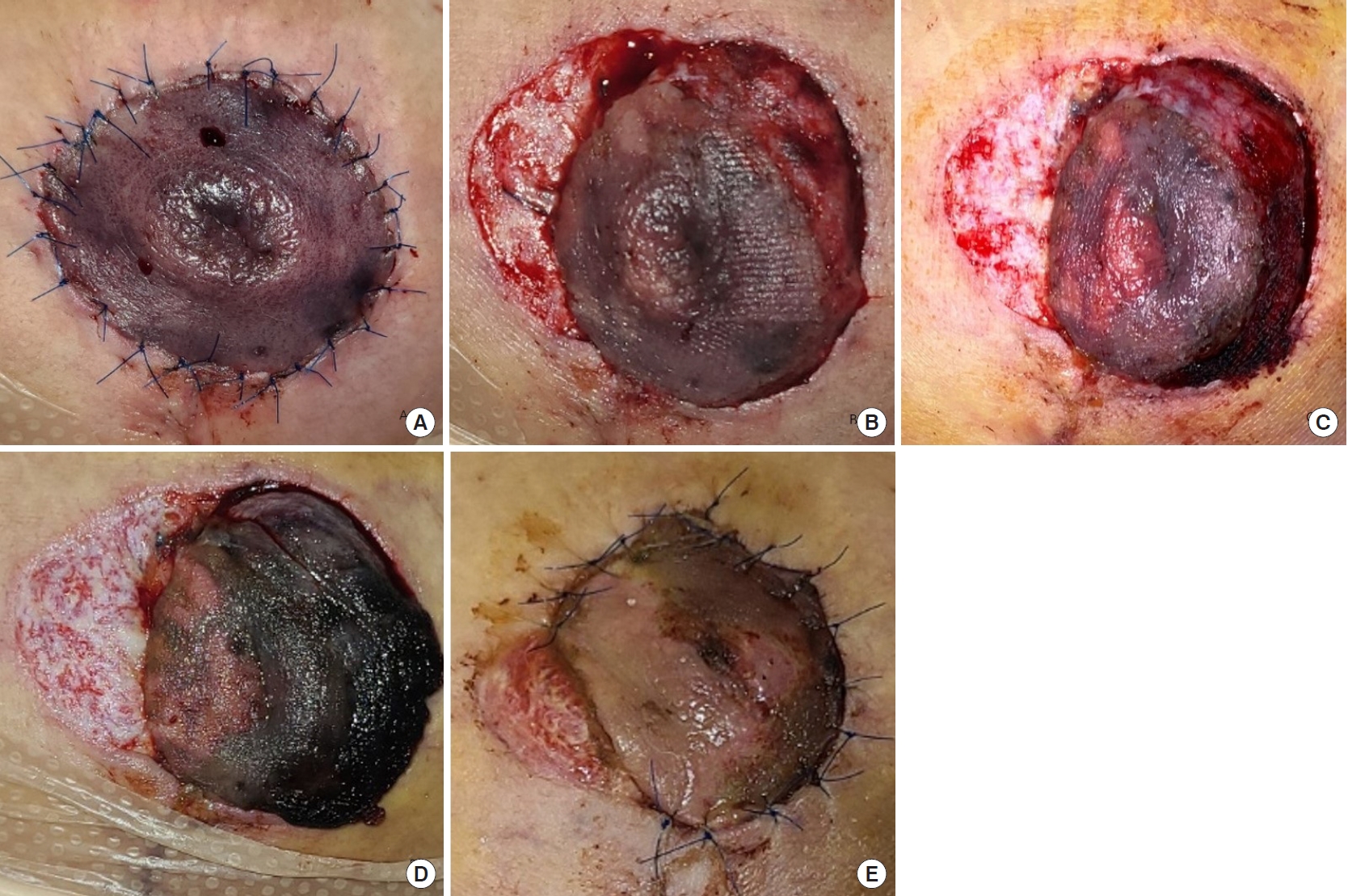

Daily dressing was performed, and neither NAC displayed any signs of venous congestion at 20 hours and 28 hours postoperatively. Venous congestion was first noticed 40 hours after surgery, when bluish discoloration and delayed dark sanguineous bleeding upon pinpricking were observed (Fig. 3A). The patient was reluctant to use leeches; hence, all peri-areolar stitches were removed promptly. Intravenous lipo-prostaglandin E1 (Eglandin; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Hwaseong, Korea) administration and nitroglycerin cream (Pasarect; Dae Hwa Pharmaceutical, Hoengseong, Korea) application were started. The discoloration did not resolve, and the wound was managed with a thorough cleansing with povidone-iodine followed by placement of an aseptic, occlusive dressing to prevent secondary infection.

Nonetheless, the NAC progressively became darker from postoperative day (POD) 2 through 4 and 6 (Fig. 3). When the patient was discharged on POD 8, a portable, single-use negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) device (PICO; Smith and Nephew Healthcare, Hull, UK) was applied for 3 weeks (from POD 8 to 30) to promote angiogenesis, reduce scarring, and minimize dressing changes after discharge.

Discoloration of the NAC resolved by POD 13 (Fig. 3E). Staged delayed sutures were performed at our outpatient clinic; the lateral two-thirds of the area was sutured on POD 8, while the remnant area was sutured after debridement on POD 23. One month after the operation, the symmetry of the breasts and nipple projection were well maintained, and the NAC was salvaged with minimal hypertrophic scarring on the medial side (Fig. 1B).

Any indication of vascular compromise of the NAC during or immediately after reduction mammoplasty warrants exploration. Possible causes of NAC ischemia are torsion of the pedicle, pedicle constriction due to a tight skin envelope or underlying hematoma, or inadequate venous drainage [6,7]. Several known risk factors are also associated with NAC ischemia, including large-volume resection, repositioning of the NAC by more than 15 cm in length, obesity, and age greater than 30 years [8-10].

In most cases, NAC congestion is discovered after inset of the NAC or within a couple of hours of the operation. In our case, however, venous congestion was discovered 48 hours after the operation. The risk factors relevant to our patient were obesity (BMI of 30.7 kg/m2), the large volume of reduction (634 g and 628 g), and NAC transposition length exceeding 15 cm (16ŌĆō17 cm). Deoxygenation of blood usually occurs within 30 minutes of venous compromise [11], leading to discoloration of the flap. The progression of venous congestion in our case was atypical. Furthermore, only flaps with complete venous obstruction become progressively darker over time [12], whereas partial venous occlusion (<50% reduction) causes subtle color changes that often remain undetected until discoloration becomes more evident [11].

In our patient, the NACs were evaluated 20, 28, and 40 hours after the operation, and color change and mild edema were first recognized 40 hours postoperatively. Partial venous congestion may have developed during the first 20ŌĆō28 hours postoperatively, causing the color to change to a relatively minimal extent. However, as edema worsened, venous congestion was aggravated, as shown by the progressive discoloration of the NAC from POD 2 through 6 (Fig. 3). Progressive obstruction of the venous drainage aggravated by edema near the pedicle was the likely culprit of delayed venous congestion of the NAC in our patient.

Several treatment options are available for NAC ischemia. If the ischemia is found intraoperatively, kinking or compression of the pedicle, hematoma, or injury to the vasculature itself are possible causes. To reduce skin tension, additional parenchymal resection can be performed. If circulation is not restored even after additional resection, peri-areolar sutures are removed, and delayed sutures can be performed over the next few days or even weeks [3]. However, delayed suturing may cause widening of the peri-areolar scars. If congestion persists even after suture removal, conversion to a free nipple graft is also an option. However, loss of nipple sensation and lactation function are the drawbacks [9].

When compromised NAC vascularity is not identified in the early postoperative period, conservative wound care is indicated, followed by delayed NAC reconstruction after complete healing [13]. More recently, other treatment options have been introduced for postoperatively identified NAC congestion. The use of Hirudo medicinalis to alleviate venous congestion of the NAC has also been proposed [7]. However, leech application has the drawback of potential soft tissue infection [14]. NPWT can also be utilized to increase the vascularity of the NAC through angiogenesis and to reduce edema [4]. Its use in breast surgery is gaining more popularity and it has been shown to reduce mastectomy skin flap necrosis [15]. Application of nitroglycerin ointment or intravenous administration of prostaglandin can promote venous drainage through vasodilation [5,16]. If all methods fail and partial or complete necrosis of the NAC is inevitable, healing by secondary intention may also be used with satisfactory outcomes depending on the patient [17].

In our patient, NAC discoloration was identified relatively late. According to previous algorithms, the treatment suggested for NAC discoloration detected more than 6 hours postoperatively is wound care with the expectation of partial or total necrosis [13]. With combination therapy using suture removal followed by delayed suturing, application of nitroglycerin cream, and the use of portable NPWT, the patientŌĆÖs NAC was salvaged with satisfactory nipple projection and minimal scarring. The use of NPWT promoted angiogenesis and faster wound contraction, thereby minimizing the widening of the peri-areolar scar associated with delayed closure.

At many clinics and hospitals, reduction mammoplasty is often performed as an outpatient operation, with no significant difference in complications compared to procedures requiring longer hospitalization [18]. Although very uncommon, delayed NAC ischemia can occur without any intraoperative event, as was the case in our patient. In high-risk patients, prolonged hospitalization is recommended for early detection and prompt management.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of her images.

Fig.┬Ā1.

Medical photographs. (A) Preoperative medical photograph. (B) Medical photograph taken 30 days postoperatively, showing complete healing of the left nipple-areolar complex with minimal scarring.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Progression of congestion of left nipple-areolar complex. (A) Postoperative day 2 (48 hours postoperatively). (B) Postoperative day 2, after peri-areolar stitch removal. (C) Postoperative day 4. (D) Postoperative day 6, aggravation of discoloration on the lateral side. (E) Postoperative day 13, partial resolution of discoloration.

REFERENCES

1. Serletti JM, Reading G, Caldwell E, et al. Long-term patient satisfaction following reduction mammoplasty. Ann Plast Surg 1992;28:363-5.

2. Greco R, Noone B. Evidence-based medicine: reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139:230e-239e.

3. Hallock GG, Cusenz BJ. Salvage of the congested nipple during reduction mammoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1986;10:143-5.

4. Erba P, Rieger UM, Pierer G, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) for venous congestion of the nipple-areola complex. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61:852-4.

5. Handel N, Yegiyants S. Managing necrosis of the nipple-areolar complex following reduction mammaplasty and mastopexy. In: Shiffman MA, editor. Nipple-areolar complex reconstruction: principles and clinical techniques. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2008. p. 629-41.

6. OŌĆÖDey DM, Demir E, Pallua N. The bivectorial full-thickness superiorly based NAC flap: a new option to increase plasticity and decrease tension in the superior pedicle vertical mammaplasty technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2008;32:802-6.

7. Freeman M, Carney M, Matatov T, et al. Leech (Hirudo medicinalis) therapy for the treatment of nipple-areolar complex congestion following breast reduction. Eplasty 2015;15:ic45.

8. Gravante G, Araco A, Sorge R, et al. Postoperative wound infections after breast reductions: the role of smoking and the amount of tissue removed. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2008;32:25-31.

9. Wray RC, Luce EA. Treatment of impending nipple necrosis following reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1981;68:242-4.

10. Blomqvist L. Reduction mammaplasty: analysis of patientsŌĆÖ weight, resection weights, and late complications. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1996;30:207-10.

11. Le Roux CM, Pan WR, Matousek SA, et al. Preventing venous congestion of the nipple-areola complex: an anatomical guide to preserving essential venous drainage networks. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:1073-9.

12. Russell JA, Conforti ML, Connor NP, et al. Cutaneous tissue flap viability following partial venous obstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:2259-68.

13. Rancati A, Angrigiani C. Nipple-areolar complex ischemia: management during aesthetic mammoplasties. In: Shiffman MA, editor. Nipple-areolar complex reconstruction: principles and clinical techniques. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2008. p. 233-44.

14. Hwang K, Kim HM, Kim YS. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus following leech application at a congested flap after a mastectomy. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2017;23:143-5.

15. Kim JH, Kim YS, Kim YW, et al. A single-use negative-pressure wound therapy device can reduce mastectomy skin flap necrosis in direct-to-implant breast reconstruction. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2020;26:12-9.

16. Choi JA, Lee KC, Kim MS, et al. Comparison of prostaglandin E1 and sildenafil citrate administration on skin flap survival in rats. Arch Craniofac Surg 2015;16:73-9.

-

METRICS

- Related articles in AAPS

-

Treatment of complications after augmentation mammoplasty.2000 March;6(1)