|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 24(1); 2018 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM) are a common form of hyperpigmentation in Asian populations, characterized by brownish-blue or slate-gray pigmentation in the bilateral malar regions. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and complications of a Q-switched (QS) fractional ruby laser in the treatment of ABNOM.

Methods

Forty-four patients with ABNOM treated with a QS fractional ruby laser from January 2014 to February 2016 were enrolled in this study. Patients received up to 10 treatment sessions, at intervals ranging from 3 to 4 weeks. An automatic skin diagnosis system was used before and after laser treatment to evaluate the efficacy of the laser treatment. To evaluate the complications of the laser treatment, a retrospective chart review was conducted.

Results

Forty-one patients were female, and 3 were male. The mean age of the patients was 47.2 years, and the mean follow-up period was 14 months. The median skin pigmentation score was 5 (interquartile range [IQR], 5–6) before laser treatment and 3 (IQR, 3–4) after laser treatment. A statistically significant difference (P < 0.01) was found in the skin pigmentation score before and after laser treatment.

Acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM) are a common form of hyperpigmentation in Asian populations, characterized by small, bilateral, blue-brown and/or slate-gray patches on the forehead, temples, eyelids, malar areas, and alae and roots of the nose [1]. As reported in other studies, several treatment modalities, including cryotherapy and dermabrasion, have been tried for ABNOM [2,3]. Based on the principles of selective photothermolysis, nevus of Ota has been successfully treated with Q-switched (QS) ruby lasers, QS alexandrite lasers, and QS neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet lasers (QS-Nd:YAG) [4-7]. ABNOM and nevus of Ota, are histologically similar, which suggested to us that laser therapy may also be successful for treating ABNOM. We therefore assessed the efficacy and complications of a fractional QS ruby laser (QSRL) in the treatment of ABNOM. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and complications of QSRL in the treatment of ABNOM.

Of the patients who underwent ABNOM treatment using a QSRL between January 2014 and February 2016, 44 patients who could be observed throughout a follow-up of longer than 12 months were enrolled in this study. Patients who had active systemic or local infections, local skin disease that might have altered wound healing, a history of psychiatric illness, or soft tissue augmentation material in face were excluded from this study.

Patients’ medical charts and operative records were reviewed retrospectively to evaluate postoperative outcomes and complications. This study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from each patient for the both the laser treatment and the publication of photographs of the results.

In all patients, we applied a 5% lidocaine topical anesthetic ointment (Emla®; AstraZeneca AB, Karlskoga, Sweden) to the full facial area before the QSRL treatment. The topical anesthetic ointment was washed off with mild soap and water immediately before the procedure.

A total of 44 patients were treated with a QSRL (Melastar; Asclepion Laser Technologies, Jena, Germany), at a wavelength of 694 nm, a pulse duration of 25 ns, a spot size of 3 to 4 mm, and a fluence of 4.5 to 6 J/cm2. The level of laser fluence was determined by the coloration of the lesion. The therapeutic endpoint was immediate whitening following laser irradiation. The energy density was reduced if tissue bleeding was prominent. Patients received up to 10 treatment sessions, at intervals ranging from 3 to 4 weeks.

After each laser treatment session, a topical antibiotic ointment was applied to the area irradiated by the QSRL. All patients were instructed to avoid direct sunlight and to apply a sunblock agent between laser treatment sessions in order to minimize post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. A depigmentation cream, such as a 4% hydroquinone cream, was applied when post-laser hyperpigmentation occurred. The patients were instructed to visit in our hospital promptly if they encountered any other adverse effects.

We evaluated the patients using an automatic skin diagnosis system (A-One Lite®; BOMTECH Electronics Co., Seoul, Korea) before treatment and 6 months after treatment. The automatic skin diagnosis system evaluated skin laxity using a scanner, and graded sagging and laxity on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher skin grade scores indicating more severe sagging and laxity. The A-One Lite scoring system comprehensively calculated a pigmentation score, including skin pore and sebum pigment condition. The clinician investigated color and possible hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation after treatment.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Friedman test was used to compare the skin test scores of patients before treatment and 6 months after treatment. All P-values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Of the 44 patients who were treated using a QSRL, 41 were female and 3 were male (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 47.2 years (range, 25–67 years) and the mean follow-up period was 14 months (range, 12–16 months).

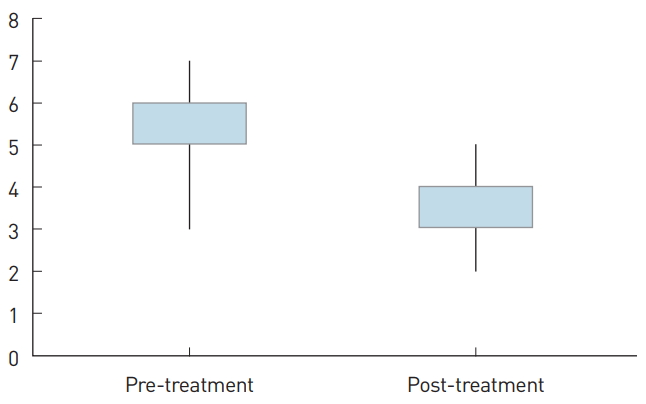

The median skin grade score was 5 (interquartile range [IQR], 5–6) before treatment, and 3 (IQR, 3–4) 6 months after treatment (Fig. 1 and Table 2). This decrease in the skin grade score was statistically significant (P<0.01).

Major complications of QSRL treatment, such as scarring and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation, were not observed during the follow-up period (Fig. 2-4). The most frequent minor complication was immediate mild erythema in the treated area. This transient erythema disappeared within 24 to 48 hours after treatment.

Hori et al. [1] initially described ABNOM, also referred to as Hori nevi, in 1984. ABNOM usually begin as discrete brown macules, which become confluent, slate-gray macules over time [8]. The malar region of the cheek is the most commonly affected site on the face.

It is important to clinically and histologically differentiate ABNOM from nevus of Ota and female facial melasma. Histologically, there are irregularly shaped, bipolar melanocytes dispersed in the papillary and mid-dermis regions, particularly in the subpapillary dermis, with no disturbance of the normal skin architecture. In contrast, melanocytes in nevus of Ota are distributed diffusely throughout the papillary and reticular dermis [9]. ABNOM are an acquired disorder, usually appearing at 40 to 50 years of age, and are usually bilateral. In contrast, nevus of Ota usually develops during the first year of life or during adolescence, is usually unilateral, and involves the conjunctival, oral, or nasal mucosae. Although dermabrasion has been successful in the treatment of ABNOM, this procedure is highly invasive and is associated with many complications, including scarring, infection, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation [3].

There are some differential diagnoses of ABNOM, especially in acquired cases with adult onset, such as melasma or lentigines, which are other adult-onset pigmentary disorders appearing on the face. These conditions show a variety of clinical features in terms of color, distribution, size, and onset.

Melasma is classified into epidermal, dermal, and mixed types by a Wood lamp examination. Recent histopathological studies, however, have denied the presence of dermal-type melasma. Most cases of dermal-type melasma, therefore, are considered to be ABNOM, Riel melanoses, or incontinentia pigmenti histologica, which show good response to QS laser treatment. Bilateral pigmented macules in patients with adult onset, such as ABNOM, are frequently misdiagnosed as melasma. Melasma appears only on sun-exposed areas, involving post-inflammatory pigmentation after sun exposure. In melasma, therefore, the periorbital area is never involved, and the alae of the nose or the root of the nose alone is very rare, although the pigment distribution is mostly symmetrical and similar to that of ABNOM. Melasma is usually well-demarcated and uniform in color, but rarely mottled. In ABNOM, however, the border is less clear, the color contains a blue or purple-brown tint, and the pigmentation is sometimes speckled. Melasma is exacerbated by sun exposure and ameliorated by long-term sun protection, while ABNOM is rarely influenced by sun exposure. The treatments for these conditions are very different; QS lasers are the only choice for the treatment of adult-onset dermal melanocytosis, while topical hydroquinone is one of the best choices for the treatment of melasma. Therefore, an accurate diagnosis is the key to successful treatment of these pigmented lesions.

Solar lentigines are usually macular lesions with a uniform shade of brown and have an irregular edge, although the size and color are variable. The distribution of ABNOM is symmetrical, but solar lentigines are not symmetrical and appear not only on the cheek, but also widely on sun-exposed areas. The border of ABNOM is less clear and the color of ABNOM contains a blue or purple-brown tint. In elderly patients, however, ABNOM can be associated with solar lentigines.

The QSRL was the first laser reported to be highly efficacious for the treatment of benign epidermal pigmented lesions [10]. The 694-nm wavelength allows for deeper penetration, thereby improving dermal pigmentation, as seen with nevus of Ota [11]. The 694-nm wavelength of QSRLs is more strongly absorbed and more selective for melanin than the wavelength of QS-Nd:YAG (1,064 nm), so QSRL is expected to be more effective than QS-Nd:YAG for the treatment of ABNOM. The collective experience of over 2 decades and the well-documented efficacy of QSRLs against epidermal and dermal pigmentation make this laser an ideal first-line choice. Therefore, QS lasers are the main treatment method for both ABNOM and nevus of Ota. In a previous study, of patients undergoing 2-7 QS-Nd:YAG laser treatment sessions at intervals of 2 to 6 months, 30% to 100% showed an improved response, with differences in clinical responses due to differences in laser parameters and treatment intervals [12-14].

In our treatment, all patients who were treated for 10 sessions showed a higher than median skin grade score. We found a statistically significant correlation between the number of treatments and the therapeutic outcome. This means that clinicians need to consider repeated treatments for resolving ABNOM. We found no color or site-dependent differences in therapeutic outcomes. In contrast to several previous protocols, our repetitive treatment sessions were performed at 3 to 4 week intervals. This short interval time was chosen to improve the rate of clearing and to prevent epithelial repigmentation. Epidermal melanin and melanocytes are competing chromophores for dermal pigment laser therapy and increase the risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. By performing treatment sessions at short intervals, more photons can target the dermal chromophores through the hypopigmented epithelium, while avoiding scattering of the beam [15]. In addition, heat has little effect on the hypopigmented epidermis [16]. Although the pathogenesis of ABNOM is unclear, it may be due to epidermal melanocyte migration. This mechanism is consistent with the fact that the color of the macules varies with the maturity of the ABNOM. Initially, these macules are usually brown and discrete, becoming bluish-gray and diffuse over time. The early-stage brown lesions are thought to be due to the presence of melanocytes at the basal layer of the epidermis; their subsequent migration into the dermis leads to a darker bluish-gray color.

Hori macules, or ABNOM, have also been reported to variably respond to different lasers, including QSRL, QS-Nd:YAG, QS alexandrite, and a combination of a CO2 laser and QSRL [12,14,17-19]. The variation in responses across studies, including ours, may be due to several factors. First, genetic and/or environmental differences among the wide-ranging populations in Asia may modulate the apparent responsiveness to treatment. Second, operator bias may affect the parameters of treatment; in other words, some surgeons may elect to start at a higher fluence or to escalate the dosage at a more rapid rate, thereby influencing the pace of clinical improvement. Third, selection bias may play a key role in defining patient outcomes. For instance, many of the patients with ABNOM reported by Kunachak and Leelaudomlip [12] had unsuccessful prior medical and procedural treatments, and therefore may have harbored more resistant disease than our population.

Fractional-mode lasers have some advantages. The fractional mode creates a number of microscopic treatment zones (MTZs) and spares the untreated areas between MTZs. These areas of adjacent viable tissue surrounding the MTZs allow for rapid healing, resulting in shorter recovery times [13,20]. Additionally, the side effects (hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation) are less common than is seen after treatment with non-fractional lasers. In this study, the advantages of the fractional mode applied to the QSRL treatment, but multiple procedures per session and multiple treatment sessions are often required to achieve the desired clinical outcomes. This low-dose fractional-mode protocol may expose the skin to less total cumulative energy than the total toxic cumulative energy that destroys cells, leading to the lightening of ABNOM.

Our study had limitations. First, the post-treatment results were evaluated with an automatic skin diagnosis system, the reliability of which has not been established. Therefore, errors may have occurred in terms of how the automatic skin diagnosis system assessed the actual skin conditions. Second, our study did not include a histologic evaluation. Therefore, further studies including a histologic analysis should be conducted, and we are planning such research. Third, our study used a fractional laser, so multiple treatment sessions were required. Despite these limitations, the significance of our study is that the efficacy of a QS 694-nm ruby fractional laser was proven through an objective analysis.

Although multiple sessions are required, we provide evidence that the use of multiple treatment sessions of a QS 694-nm ruby fractional laser can be an effective and less invasive strategy for the treatment of ABNOM. The length of follow-up after the final treatment was only 12 months, so long-term safety and efficacy follow-up studies of this treatment protocol are needed.

Fig. 1.

The median skin grade score was 5 (interquartile range [IQR]: 5–6) before treatment, and the median skin grade score was 3 (IQR: 3–4) at 6 months after treatment.

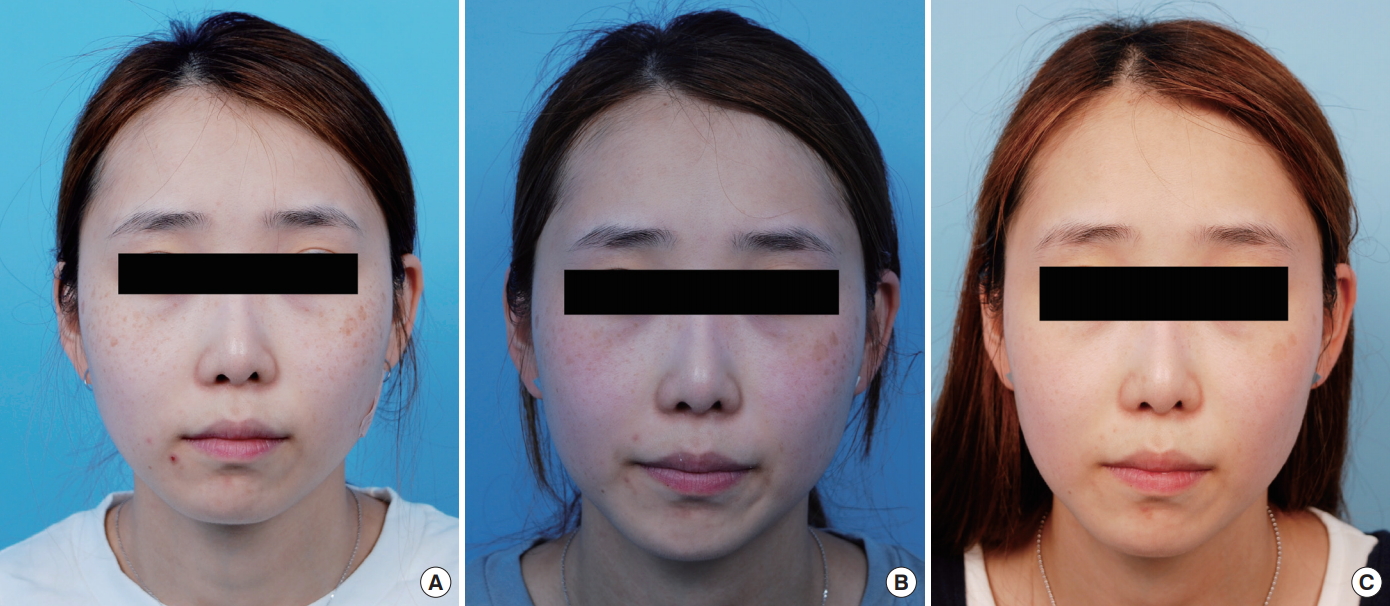

Fig. 2.

A 26-year-old female patient with acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. (A) Before treatment, she was examined by the automatic skin diagnosis system and had a skin grade score of 6. (B) After 5 treatment sessions. (C) After the final treatment, her skin grade score was 2.

Fig. 3.

A 33-year-old female patient with acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. (A) Before treatment, she was examined by the automatic skin diagnosis system and had a skin grade score of 5. (B) After 5 treatment sessions. (C) After the final treatment, her skin grade score was 3.

Fig. 4.

A 48-year-old female patient with acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. (A) Before treatment, she was examined by the automatic skin diagnosis system and had a skin grade score of 6. (B) After the final treatment, her skin grade score A B was 4.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 41 (93.2%) |

| Male | 3 (6.8%) |

| Age (year), mean (range) | 47.2 (25–67) |

Table 2.

Skin pigmentation scores

| Time | Pre-treatment (median) | Post-treatment (median) | P-valuea) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin pigmentation score | 5 (IQR: 5–6) | 3 (IQR: 3–4) | <0.01 |

REFERENCES

1. Hori Y, Kawashima M, Oohara K, et al. Acquired, bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10:961-4.

2. Hori Y, Takayama O. Circumscribed dermal melanoses. Classification and histologic features. Dermatol Clin 1988;6:315-26.

3. Kunachak S, Kunachakr S, Sirikulchayanonta V, et al. Dermabrasion is an effective treatment for acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. Dermatol Surg 1996;22:559-62.

4. Chan HH, Ying SY, Ho WS, et al. An in vivo trial comparing the clinical efficacy and complications of Q-switched 755 nm alexandrite and Q-switched 1,064 nm Nd:YAG lasers in the treatment of nevus of Ota. Dermatol Surg 2000;26:919-22.

5. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of nevus of Ota by the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg 1995;21:592-6.

6. Goldberg DJ, Nychay SG. Q-switched ruby laser treatment of nevus of Ota. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1992;18:817-21.

8. Ee HL, Wong HC, Goh CL, et al. Characteristics of Hori naevus: a prospective analysis. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:50-3.

9. Park JM, Tsao H, Tsao S. Acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (Hori nevus): etiologic and therapeutic considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;61:88-93.

10. Taylor CR, Anderson RR. Treatment of benign pigmented epidermal lesions by Q-switched ruby laser. Int J Dermatol 1993;32:908-12.

11. Taylor CR, Flotte TJ, Gange RW, et al. Treatment of nevus of Ota by Qswitched ruby laser. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:743-51.

12. Kunachak S, Leelaudomlipi P. Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment for acquired bilateral nevus of ota-like maculae: a long-term follow-up. Lasers Surg Med 2000;26:376-9.

13. Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Review of the literature: treatment of dyspigmentation with fractionated resurfacing. Dermatol Surg 2010;36:1499-508.

14. Polnikorn N, Tanrattanakorn S, Goldberg DJ. Treatment of Hori’s nevus with the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg 2000;26:477-80.

15. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE, Goldman MP. Treatment of facial skin using combinations of CO2, Q-switched alexandrite, flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye, and Er:YAG lasers in the same treatment session. Dermatol Surg 2000;26:114-20.

16. Lee B, Kim YC, Kang WH, et al. Comparison of characteristics of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules and nevus of Ota according to therapeutic outcome. J Korean Med Sci 2004;19:554-9.

17. Manuskiatti W, Sivayathorn A, Leelaudomlipi P, et al. Treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (Hori’s nevus) using a combination of scanned carbon dioxide laser followed by Q-switched ruby laser. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:584-91.

18. Kunachak S, Leelaudomlipi P, Sirikulchayanonta V. Q-Switched ruby laser therapy of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. Dermatol Surg 1999;25:938-41.

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 7,523 View

- 134 Download

- Related articles in AAPS