|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 24(3); 2018 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Donor site seroma is the most frequent and troublesome complication of latissimus dorsi (LP) flaps. This study aimed to identify the risk factors of seroma formation after an LD flap and to evaluate the biochemical composition of seromas.

Methods

The medical records of 84 patients who underwent an LD flap from September 2007 to May 2017 were reviewed. Age; body mass index (BMI); the type of breast surgery, reconstruction, and nodal dissection; the usage of fibrin glue; smoking; chemotherapy; and history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension were evaluated. In 11 of the 84 patients, the levels of electrolytes, glucose, proteins, lipids, and inflammatory markers present in seromas were investigated.

Results

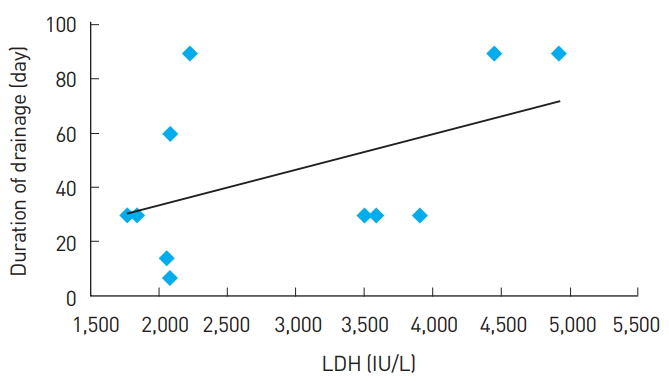

The overall incidence of seroma was 66.7%. Advanced age (Ōēź45 years) and overweight (BMI Ōēź23 kg/m2) were significant risk factors for seroma. Patients who underwent an extended LD flap had a higher incidence of seroma than those who underwent a standard LD flap, while those who underwent breast-conserving surgery had a lower incidence of seroma than those who underwent other breast procedures. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in seromas on postoperative day 2 demonstrated a positive linear correlation with the duration of drainage, but this relationship did not reach statistical significance.

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in Korea, following thyroid cancer. From 1999 to 2013, the incidence of breast cancer increased from 6,025 patients per year to 20,159 [1]. Many of these women undergo breast cancer surgery, and an increasing number elect to pursue breast reconstruction. In fact, the frequency of breast reconstruction surgery, of which there were 99 cases in 2000, increased by more than 10 times to 1,111 cases in 2013 [2]. Since it was first described in the late 1970s, the latissimus dorsi (LD) musculocutaneous flap has been frequently used as a primary method of immediate and delayed breast reconstruction [3,4]. The LD flap has become a preferred method of breast reconstruction due to its low donor site morbidity, reliable vascularity, and the fact that it does not require microvascular procedures. Additionally, the rate of flap and donor site complications is lower than observed with other flaps, such as the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap, which has a higher risk of partial necrosis [5]. Nonetheless, as with other reconstructive flaps, LD flaps do experience some complications. The most common complication is donor site seroma, with a frequency as high as 79% [6]. Excessive seroma accumulation increases the risk of infection, wound dehiscence, and flap necrosis. Additionally, seroma causes discomfort and anxiety, frequent office visits, and increased postoperative costs [7].

Although many reports have investigated postoperative seroma formation after LD flaps, they have solely focused on identifying risk factors [5,8-10]. The purpose of this study was both to identify risk factors for seroma formation and to analyze the biochemical composition of seromas to shed further light on their nature.

In this study, 84 patients who underwent breast reconstruction using an LD flap after oncologic resection from September 2007 to May 2017 were reviewed. All operations were performed by the corresponding author. The LD flap was delicately harvested to minimize injury to the adjacent muscle. In cases where an extended LD flap was performed, lumbar fat extensions were included with the flap. The donor site was closed in layers over 2 negative suction drains. The drains were removed when the drained volume was less than 20 cc on consecutive days. No quilting sutures were performed at the donor site. After the drains were removed, if any clinically relevant seroma became apparent, we aspirated it at the outpatient department until the seroma was no longer clinically evident. In this study, seroma formation was defined as the persistence of a seroma for more than 4 weeks postoperatively. The following variables were investigated in the series of 84 patients: patient age at the time of operation, body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), smoking, chemotherapy, type of nodal dissection, usage of fibrin glue, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, the type of reconstruction (extended LD flap or LD flap), and type of breast surgery.

According to the Korean Breast Cancer Society, in 2013, breast cancer was most common in patients in their 40s. Therefore, in this study, patients were divided into 2 groups based on the cut-off of 45 years of age [2].

Patients with a BMI of less than 23 kg/m2 were classified as normal or underweight, and patients with a BMI of greater than or equal to 23 kg/m2 were classified as overweight, according to the 2,000 proposal of the Regional Office for the Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization. According to this proposal, in Asian adult populations, overweight should be classified as a BMI of more than 23 kg/m2 and obesity should be defined as a BMI of over 25 kg/m2 [10,11]. In 11 of the 84 patients, seroma fluid samples were acquired from the drains or aspiration. The samples were directly kept in a deep freezer (ŌłÆ80┬░C) at the Human Bio Resource Bank of our institution. After informed consent was provided, and using Institutional Review BoardŌĆōapproved protocols, the specimens were collected and assayed in a clinical laboratory. Samples obtained at 2, 7, and 14 days after the operation were analyzed, and if there were any samples obtained at 1, 2, or 3 months after the operation, they were also analyzed. Levels of electrolytes, glucose, proteins, lipids, and inflammatory markers were evaluated. To distinguish whether seroma was transudate or exudate, LightŌĆÖs criteria [12] were applied. According to LightŌĆÖs criteria, the presence of any of the following 3 characteristics indicates that fluid is an exudate: a fluid to serum protein ratio greater than 0.5, a fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level greater than 200 IU, and a fluid to serum LDH ratio greater than 0.6.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R (version 3.1.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The data were analyzed using the Žć2 test. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

The overall data for the incidence of donor site seroma are summarized in Table 1. Our patientsŌĆÖ average age was 45.6 years (range, 24ŌĆō84 years), and their average BMI was 23.36 kg/m2 (range, 17.62ŌĆō39.12 kg/m2). Among the 84 patients, 56 (66.7%) developed a postoperative seroma. Patients older than 45 years had a significantly higher incidence of seroma (37 of 46 patients, 80.4%) than those younger than 45 years of age (19 of 38 patients, 50%; P<0.05). The incidence of seroma was significantly higher in patients with a BMI Ōēź23 kg/m2 (34 of 39 patients, 87.2%) than in those with a BMI <23 kg/m2 (22 of 45 patients, 48.9%; P<0.05). Patients who underwent an extended LD flap had a higher incidence of seroma (34 of 40 patients, 85%) than those who underwent a standard LD flap (22 of 44 patients, 50%; P<0.05).

Patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery demonstrated a lower incidence of seroma (7 of 20 patients, 35%) than those who underwent total mastectomy (4 of 6 patients, 66.7%), radical mastectomy (1 of 1 patient, 100%), modified radical mastectomy (6 of 9 patients, 66.7%), or skin-sparing mastectomy (38 of 48 patients, 79.2%; P<0.05).

Other variables, such as smoking, chemotherapy, type of nodal dissection, usage of fibrin glue, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, did not affect the incidence of seroma formation.

All patients were monitored regularly until no further aspiration was needed. Despite continued aspiration, 7 patients (8.3%) required surgical treatment due to a prolonged seroma. The mean duration of drainage was 72.7 days (range, 9ŌĆō655 days).

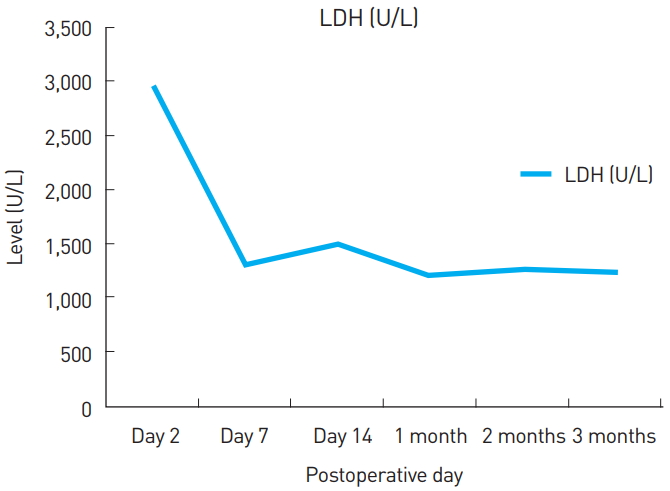

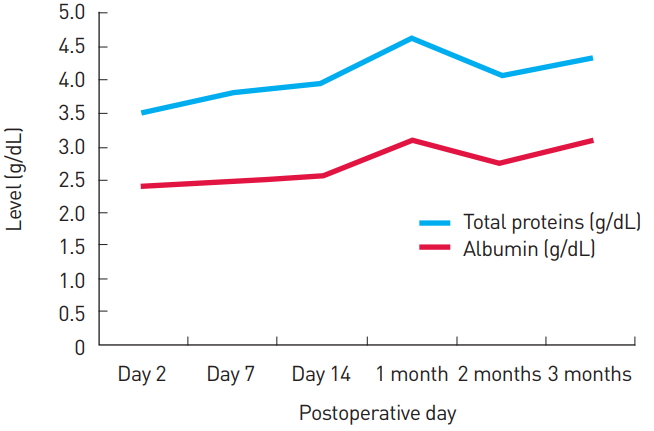

In 11 of the 84 patients, the biochemical composition of the seroma fluid was analyzed. The seromas all met LightŌĆÖs criteria for being an exudate. The LDH values were highest on the second day after the operation and gradually decreased over time, while total protein and albumin values tended to increase over time (Table 2, Fig. 1 and 2). However, other laboratory values, such as levels of electrolytes, glucose, and cholesterol, did not show any clearly discernable patterns of change.

In patients who experienced seroma formation, the level of LDH from the seroma on postoperative day 2 was higher than in those who did not (Fig. 3). The LDH level in the seroma on postoperative day 2 demonstrated a positive linear correlation with the duration of drainage, but it was not significant (correlation coefficient, 0.57; P=0.07). Nonetheless, the LDH level in the seroma on postoperative day 2 showed a predictable linear relationship with the duration of drainage on a scatter diagram (Fig. 4). Higher levels of LDH in the seroma on postoperative day 2 may be correlated with a longer duration of drainage.

The LD flap is widely used because of its advantages such as reliable vascularity, proximity to the defect, and relative simplicity in dissection [10,13]. Despite all these advantages, donor site seroma is a common and troublesome complication of LD flaps. Several methods, such as quilting sutures [14-16], fibrin glue [6], and triamcinolone [17], have been used in attempts to reduce the incidence of seroma. Although these procedures have some positive effects on reducing the incidence of seroma, they also increase the operating time and hospital costs. Therefore, it would be more reasonable to use these techniques selectively in patients at high risk of seroma than to use them for all patients.

The incidence of seroma formation in this study was 66.7%, which falls within the 11.8% to 79% range reported in other papers [5]. Previous studies have reported that older age, obesity [5,9,10], wider excision or mastectomy [5], and nodal dissection [18] were risk factors for seroma formation. Indeed, in this study, patients older than 45 years had a significantly higher incidence of donor site seroma than patients younger than 45 years. Overweight patients had a higher incidence of seroma than underweight patients, and patients who underwent a procedure with less excision, such as breast-conserving surgery, had a lower incidence of seroma than those who underwent a wider excision or mastectomy. Additionally, patients in whom an extended LD flap was used had a higher incidence of seroma than those in whom a standard LD flap was used.

There are several possible explanations for these results. The cause of seroma is multifactorial, involving the disruption of lymphatic and vascular channels, shearing effects between subcutaneous surfaces and the underlying muscle, surgically created dead space, and mediators of inflammation [6]. Wider excision or mastectomy leaves a larger defect, requiring a larger flap to cover it. This results in a wide dissection, more tissue injury, and a larger dead space at the donor site. The same explanation can be applied to obese patients because they generally have a larger breast volume than non-obese patients.

Randolph et al. [18] reported that patients who underwent axillary nodal or sentinel nodal dissection had a higher incidence of seroma (22 of 42 patients, 52%) than those who underwent no nodal dissection (2 of 8 patients, 25%), but this relationship was not statistically significant. Similarly, in this study, the patients who underwent nodal dissection had a higher incidence of seroma (axillary nodal dissection, 67.9% and sentinel nodal dissection, 68.8%) than those who underwent no nodal dissection (50%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Factors influencing seroma formation have been reported in previous studies. Weinrach et al. [6] reported that the application of fibrin sealant could reduce the seroma rate. However, in this study, no statistically significant decrease in the seroma rate was associated with the use of fibrin glue. Further large-scale studies with long-term follow-up are required to evaluate these issues conclusively.

Unlike other studies, this study analyzed the biochemical composition of seromas. When evaluating a sample of human bodily fluid, classifying it as either a transudate or an exudate is the first diagnostic step. This provides clinicians with important information for understanding the pathophysiology of the fluid. Exudates are fluids rich in protein and cellular elements that ooze from blood vessels because of inflammation. The altered permeability of blood vessels permits the passage of large molecules and solid matter through their walls. By comparison, transudates are fluids that pass through a membrane, which filters out many of the proteins and cellular elements and yields a watery solution. The process of transudation is attributable to increased pressure in the veins and capillary pressure forcing fluid through the vessel walls [7]. The most commonly used method for differentiating exudates from transudates was established by Light et al. [12] and G├Īzquez et al. [19]. Although those studies were conducted for pleural effusions, the resulting criteria are currently accepted for almost any fluid accumulation in the body [7,20-22]. In this study, in accordance with LightŌĆÖs criteria, all seroma fluids appeared to be exudates. Furthermore, the seroma fluid continued to meet the criteria for being an exudate over time.

Seroma was originally considered to be the result of a pure lymphatic obstruction, constituting an accumulation of lymph [21]. However, the seroma fluid analyzed in this study had a higher level of large molecules, such as albumin and globulin, than is generally found in lymph. Additionally, the levels of LDH and cholesterol were significantly higher than in lymph [7].

LDH is a cytoplasmic enzyme present in essentially all major organ systems. The extracellular appearance of LDH is due to cell death caused by phenomena such as inflammation, ischemia, and dehydration. Therefore, LDH levels are used to detect cell damage or cell death [23]. In this study, the LDH levels from seroma fluid were highest on the second day after the operation and then declined. In patients with seroma that lasted more than 4 weeks, LDH levels tended to be higher on postoperative day 2 than in patients with a seroma that lasted less than 4 weeks. Additionally, the LDH from seroma on postoperative day 2 demonstrated a positive linear correlation with the duration of drainage. Therefore, higher levels of LDH, which are associated with inflammation, on the second day after the operation were associated with a greater likelihood that the seroma would last for a long time.

In terms of its biochemical composition, seroma after breast reconstruction using an LD flap is similar to inflammatory exudates, instead of just being a collection of serum (transudate) or lymph. Exudate is an element of acute inflammatory reactions (i.e., the first phase of wound repair). Therefore, seroma formation reflects an increased intensity and prolongation of this phase [24].

If seroma fluid accumulates in the form of an inflammatory exudate, the size of the dead space, tissue handling during the operation, and the extent of undermining are factors that may significantly affect postoperative fluid collection.

There are several limitations of this study. It was retrospective in nature and therefore subject to confounding errors. Additionally, it was only possible to perform biochemical analyses of seromas in 11 of the 84 patients because not all patients visited on the exact dates necessary and some were lost to follow-up.

Significant risk factors for seroma formation after an LD flap included advanced age, overweight, wider excision or mastectomy, and the use of an extended LD flap. Additionally, the seromas seemed to consist of inflammatory exudate. Higher levels of LDH in seromas on postoperative day 2 may have been correlated with a longer duration of drainage. Careful flap dissection, the use of quilting sutures for reducing dead space, and gentle tissue handling should be considered, especially in high-risk patients.

Fig.┬Ā1.

Changes in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values over time. The LDH values were highest on the second day after the operation and gradually decreased over time.

Fig.┬Ā2.

Changes in total protein and albumin values over time. The total protein and albumin values tended to increase over time.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Changes in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values over time in patients with seroma formation and without seroma formation. In patients with seroma formation, the level of LDH in the seroma on postoperative day 2 tended to be higher than in patients without seroma formation. *Seroma formation was defined as the persistence of seroma for more than 4 weeks postoperatively.

Fig.┬Ā4.

Scatter diagram depicting lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values and the duration of drainage. The scatter diagram shows a linear correlation between the duration of drainage and the LDH level in the seroma on postoperative day 2.

Table┬Ā1.

Patient demographics

| Variables | No. of cases | No. of seromas (%) | P-valuea) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 84 | 56 (66.7) | |

| Age (year) | <0.05* | ||

| ŌĆā<45 | 38 | 19 (50.0) | |

| ŌĆāŌēź45 | 46 | 37 (80.4) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <0.05* | ||

| ŌĆā<23 | 45 | 22 (48.9) | |

| ŌĆāŌēź23 | 39 | 34 (87.2) | |

| Smoking | 0.48 | ||

| ŌĆāYes | 1 | 1 (100.0) | |

| ŌĆāNo | 83 | 55 (66.3) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.54 | ||

| ŌĆāYes | 46 | 32 (69.6) | |

| ŌĆāNo | 38 | 24 (63.2) | |

| Nodal dissection | 0.57 | ||

| ŌĆāAxillary node dissection | 28 | 19 (67.9) | |

| ŌĆāSentinel node dissection | 48 | 33 (68.8) | |

| ŌĆāNone | 8 | 4 (50.0) | |

| Fibrin glue | 0.33 | ||

| ŌĆāYes | 68 | 47 (69.1) | |

| ŌĆāNo | 16 | 9 (56.3) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.00 | ||

| ŌĆāYes | 3 | 2 (66.7) | |

| ŌĆāNo | 81 | 54 (66.7) | |

| Hypertension | 0.81 | ||

| ŌĆāYes | 10 | 7 (70.0) | |

| ŌĆāNo | 74 | 49 (66.2) | |

| Type of reconstruction | <0.05* | ||

| ŌĆāExtended LD flap | 40 | 34 (85.0) | |

| ŌĆāLD flap | 44 | 22 (50.0) | |

| Type of breast surgery | <0.05* | ||

| ŌĆāTotal mastectomy | 6 | 4 (66.7) | |

| ŌĆāRadical mastectomy | 1 | 1 (100.0) | |

| ŌĆāModified radical mastectomy | 9 | 6 (66.7) | |

| ŌĆāBreast conservative surgery | 20 | 7 (35.0) | |

| ŌĆāSkin sparing mastectomy | 48 | 38 (79.2) |

Table┬Ā2.

Mean┬▒standard error of the mean concentration of the different elements in post-latissimus dorsi flap seroma fluid

REFERENCES

1. Park EH, Min SY, Kim Z, et al. Basic facts of breast cancer in Korea in 2014: the 10-year overall survival progress. J Breast Cancer 2017;20:1-11.

2. Korean Breast Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2016. Seoul: Korean Breast Cancer Society; 2016.

3. Schneider WJ, Hill HL Jr, Brown RG. Latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap for breast reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg 1977;30:277-81.

4. In: Grotting JC, Neligan PC. editors. Plastic surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

5. Tomita K, Yano K, Masuoka T, et al. Postoperative seroma formation in breast reconstruction with latissimus dorsi flaps: a retrospective study of 174 consecutive cases. Ann Plast Surg 2007;59:149-51.

6. Weinrach JC, Cronin ED, Smith BK, et al. Preventing seroma in the latissimus dorsi flap donor site with fibrin sealant. Ann Plast Surg 2004;53:12-6.

7. Andrades P, Prado A. Composition of postabdominoplasty seroma. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2007;31:514-8.

8. Porter KA, OŌĆÖConnor S, Rimm E, et al. Electrocautery as a factor in seroma formation following mastectomy. Am J Surg 1998;176:8-11.

9. Gruber S, Whitworth AB, Kemmler G, et al. New risk factors for donor site seroma formation after latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction: 10-year period outcome analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2011;64:69-74.

10. Jeon BJ, Lee TS, Lim SY, et al. Risk factors for donor-site seroma formation after immediate breast reconstruction with the extended latissimus dorsi flap: a statistical analysis of 120 consecutive cases. Ann Plast Surg 2012;69:145-7.

11. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific, International Diabetes Institute, International Association for the Study of Obesity, et al. The Asia-Pacific perspective: Redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney, AU: Health Communications Australia; 2000.

12. Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, et al. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med 1972;77:507-13.

13. Hammond DC. Latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 2007;34:75. -82. abstract vi-vii.

14. Schwabegger A, Ninkovi─ć M, Brenner E, et al. Seroma as a common donor site morbidity after harvesting the latissimus dorsi flap: observations on cause and prevention. Ann Plast Surg 1997;38:594-7.

15. Titley OG, Spyrou GE, Fatah MF. Preventing seroma in the latissimus dorsi flap donor site. Br J Plast Surg 1997;50:106-8.

16. Daltrey I, Thomson H, Hussien M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of quilting latissimus dorsi flap donor site on seroma formation. Br J Surg 2006;93:825-30.

17. Taghizadeh R, Shoaib T, Hart AM, et al. Triamcinolone reduces seroma re-accumulation in the extended latissimus dorsi donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61:636-42.

18. Randolph LC, Barone J, Angelats J, et al. Prediction of postoperative seroma after latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;116:1287-90.

19. G├Īzquez I, Porcel JM, Vives M, et al. Comparative analysis of LightŌĆÖs criteria and other biochemical parameters for distinguishing transudates from exudates. Respir Med 1998;92:762-5.

20. Lindquist L, Linn├® T, Hansson LO, et al. Value of cerebrospinal fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of meningitis: a study in 710 patients with suspected central nervous system infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1988;7:374-80.

21. Montalto E, Mangraviti S, Costa G, et al. Seroma fluid subsequent to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer derives from an accumulation of afferent lymph. Immunol Lett 2010;131:67-72.

22. Meggiorini ML, Maruccia M, Carella S, et al. Late massive breast implant seroma in postpartum. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2013;37:931-5.