Early Debridement and Cultured Allogenic Keratinocyte Dressing Prevent Hypertrophic Scarring in Infants with Deep Dermal Burns

Article information

Abstract

Background

Deep dermal burns are frequently treated with excision and skin grafting. Otherwise, wound healing may take up to 4 to 6 weeks, with serious scarring. Especially in pediatric patients, post-burn scarring could result in psychologic trauma and functional disability. We aimed to investigate the efficacy of early debridement and dressing using cultured allogenic keratinocytes in infants with deep dermal burns to prevent hypertrophic scarring.

Methods

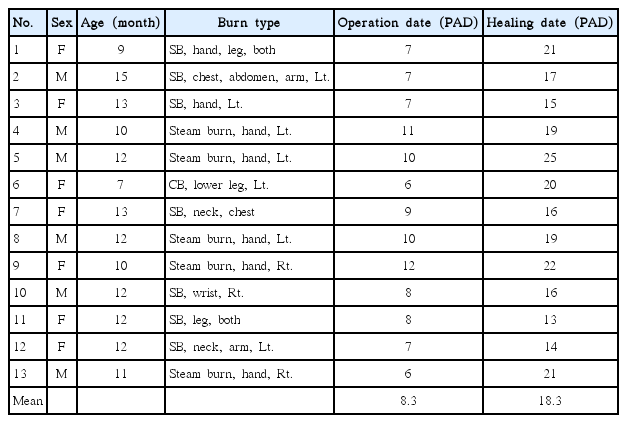

From April 2016 to April 2018, 18 infants were treated for deep dermal burns. Except for 5 infants who underwent skin grafting or excision, 13 infants were included in this study. We performed early debridement in these patients using Versajet™ and serial dressings using Kaloderm®.

Results

The average operative date was 8.3 days after the accident. The mean healing time was 18.3 days after the accident. The patients did not experience any contraction, but 3 patients had hyperpigmentation, 2 patients had mild hypertrophic scarring, and 1 patient had mixed pigmentation (hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation).

Conclusions

Our prophylactic scar therapy, using early debridement with VersajetTM and dressings with Kaloderm®, may be beneficial for infants with dermal burns. This method was able to shorten the healing time, resulting in better scar outcomes. Our follow-up findings revealed that the scars had an aesthetically pleasing appearance and patients were able to perform normal activities without restrictions.

INTRODUCTION

Burn injuries are among the most painful traumas. Even after wound healing, burn patients continue to suffer because of unsightly scars. Burn scars are not aesthetically pleasing, can restrict a patient’s normal functioning, and may lead to psychological problems. Unlike adults, pediatric patients with hypertrophic burn scars may experience psychological trauma as they grow up, and they may encounter problems with motion. These may lead them to require additional operations, resulting in further unpleasant scarring.

Given the loss of the dermis, deep dermal burns usually require surgical treatment, such as excision and skin grafting; otherwise, healing may take 4 to 6 weeks. Deep dermal burns are accompanied by a significant risk of hypertrophic scarring. Healing time is thought to be a major risk factor for the development of hypertrophic scarring. It has been demonstrated that a healing time of less than 21 days improves scar outcomes [1,2].

To minimize scar formation in burns in infants, treatment is aimed at shortening the healing time by rapidly inducing epithelization. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the efficacy of early debridement and cultured allogenic keratinocyte dressing in infants with deep dermal burns to prevent the development of hypertrophic scarring.

METHODS

Infants patients with a deep dermal burn as evaluated by a specialist from April 2016 to April 2018 were included in this study. The management strategy was based on the wound conditions, such as a more white than pink coloration, the presence of fixed dermal staining, lack of capillary refill, and a dry appearance. In cases where in the wound depth was mixed, we based our treatment strategy on the deepest level of the wound.

After several rounds of conservative treatment, we re-evaluated the wound. In cases of definitive deep dermal burns, the patients underwent early debridement surgery. Under general anesthesia, we debrided non-viable tissue with VersajetTM (Smith and Nephew, St. Petersburg, FL, USA) until pinpoint bleeding was visible, and a dressing with cultured allogenic keratinocytes was put in place (Kaloderm®; Tegoscience, Seoul, Korea). The operation time was less than 30 minutes.

Patients who did not show healing by the 30th post-accident day underwent skin grafting or local flap, and they were excluded from the study.

We calculated the healing time and assessed the condition of the scar. We informally administered the Vancouver Scar Scale to the caregivers and other medical staff. However, we did not score the scale; instead, the questions on the scale were used as a basis for the respondents to describe the scarring that they observed in the patients.

All patients underwent prophylactic scar management. We told their caregivers to massage the affected areas in order to moisturize and soften the skin until the function of the skin was restored. A pressure garment was also recommended as a follow-up therapy.

RESULTS

There were a total of 18 pediatric patients with deep dermal burns. Five patients who underwent an operation were excluded, of whom 3 underwent excision and 2 underwent skin grafting.

A total of 13 pediatric patients aged 7 to 15 months were included in this study. Seven patients had scalding burns, 5 had steam burns, and 1 had a contact burn. The average operative date was 8.3 days after the accident, and the mean healing time was 18.3 days after the accident (Table 1). The follow-up period ranged from 6 to 23 months. In the early period, 5 patients had blister formation as early as 2 to 3 weeks after discharge, but their wounds completely healed without complications. In the later period, 3 patients had hyperpigmentation, 2 had mild hypertrophic scarring (height <2 mm), and 1 had mixed pigmentation (hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation). None experienced contraction or severe hypertrophic scarring (Table 2).

Case 1

A 10-month-old boy burned the second to fifth fingers on his left hand by steam from a pressure cooker. During the initial examination, his fingers were pale in color and had a decreased refilling time. On the 3rd post-accident day, we decided to continue with conservative management after wound re-evaluation. However, on the 10th post-accident day, the fourth finger had a fixed dermal stain, whitish wound color, and dry appearance, indicating worsening conditions. Thus, we performed debridement using VersajetTM hydrosurgery and dressing with cultured allogenic keratinocytes (Kaloderm®). He was discharged on the 19th post-accident day. After 13 months, the patient had no contraction or any significant complications (Fig. 1).

Case 2

A 7-month-old girl was burned by a hot plastic bag on her right calf. On the 2nd post-accident day, the wound had a fixed dermal stain, no capillary refill time, and a dry whitish appearance. She underwent debridement on the 6th post-accident day, and her wound had completely healed on the 20th post-accident day. After 9 months, she had no scarring, but had mild hyperpigmentation (Fig. 2).

Case 3

A 12-month-old girl was burned by hot soup on her neck. She had a deep dermal burn. We performed debridement on the 7th post-accident day. She was discharged on the 14th post-accident day. At a 10-month follow-up visit, she had no significant complications (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Burn scars are painful regardless of their seriousness. They restrict the function of the body, are aesthetically unappealing, and may feel unpleasant. Patients with a post-burn scar may have aesthetic, functional, and psychological problems. In particular, infant patients experience difficulties due to scarring as they grow up.

Therefore, improving scarring is one of the most important goals of burn treatment. A lower likelihood of hypertrophic scarring is associated with a healing time of under 21 days. Healing time is therefore a primary performance indicator associated with improved scar outcomes [1,2].

Dermal burns (deep second-degree burns) are characterized by a lack of capillary refill, the presence of fixed dermal staining, decreased sensation, and a dry appearance due to damage to the microcirculation, nerves, and sweat glands. Given the loss of epidermis and partial dermis, wound healing takes weeks to months with a dressing; hence, dermal burns are usually treated with excision and split skin grafting. A significant risk of hypertrophic scarring accompanies this type of injury.

Infants have a thinner epidermis and stratum corneum and smaller corneocytes, at least until the second year of life. Thus, they are at a higher risk for deep burns than adults. Moreover, infant skin has a higher cell proliferation rate, as indicated by its smaller cell size and higher cell density [3]. Epidermal cell proliferation decreases significantly during the first year of life and reaches adult levels during the second year of life [4]. However, the higher epidermal cell proliferation rate in infants results in a shorter healing time during treatment than is possible for adults.

To shorten the healing time of the infants’ dermal burns without excision or skin grafting, we performed early debridement using VersajetTM hydrosurgery. Then, 3 to 4 days after the injury, we re-evaluated the wound and re-performed debridement. The average operation time was 8.3 days post-accident. VersajetTM is useful for obtaining the correct dermal plane and enables maximal dermal preservation, which could shorten the debridement time and reduce the bacterial burden in the wound [5-7]. The wound was also dressed with cultured allogenic keratinocytes (Kaloderm®). Kaloderm® has been reported to promote epithelization, which could help in the healing of second-degree burns [8-10], through the induction of several cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1α, IL-6, IL-8, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) and growth factors (transforming growth factor [TGF]-α, TGF-β, platelet-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor). These factors may stimulate the migration of keratinocytes from hair follicles to wound edges and the proliferation of fibroblasts [11-14]. Moreover, they also promote the release of collagenase and epidermal cell-derived factor to prevent the development of hypertrophic or contact scars [15]. The patients’ average healing time was 18.3 days post-accident.

After our prophylactic scar therapy performed in an outpatient clinic, 3 of the patients had hyperpigmentation, 2 had mild hypertrophic scarring (height <2 mm), and 1 had mixed pigmentation. The patients also underwent massage therapy and wore pressure garments as follow-up therapies, which helped reduce the risk of hypertrophic scarring, as monitored during periodic outpatient visits.

A limitation of this study is the small sample size and short-term follow-up period. However, few infants under 12 months of age experience severe dermal burns. We believe that 13 out of a total of 18 patients constitute a sufficient sample size to support our hypothesis. Because hypertrophic scarring may occur some months after injury, a previous report suggested that 6 months of follow-up would be reasonable [16]. Our follow-up period was sufficient to determine whether hypertrophic scarring appeared.

In conclusion, our prophylactic scar therapy, utilizing early debridement with VersajetTM and dressing with Kaloderm®, may be beneficial for infants with dermal burns because of their higher cell proliferation rate. This method greatly preserved the patients’ viable dermis and induced rapid epithelization, thereby shortening the healing time and achieving better scar outcomes. Our follow-up findings revealed that the scars had an aesthetically pleasing appearance, and the patients were able to perform their normal activities without restrictions.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

PATIENT CONSENT

Patients’ guardians provided written consent for the use of their images.