Reconstruction of an Extensive Atrophic Scar in the Calf Using a Free Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap

Article information

Abstract

Recently, increasing interest has emerged in contouring of the lower leg. Harmonious legs are considered one of the most important elements of women’s beauty. Calf augmentation is routinely performed using silicone implants or autologous fat grafting. However, such surgical options may be unsuitable for some patients with specific medical conditions or preferences. Herein, we report a rare case of a 36-year-old woman who selected the use of a free deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap to correct a left calf contour deformity caused by a previous gunshot injury. The free DIEP flap procedure was carried out successfully without any postoperative complications. Moreover, the patient obtained good aesthetic improvements and was satisfied with the outcome. We therefore recommend the free DIEP flap as an option for the correction of large and irregularly shaped atrophic scars in the lower leg, whether caused by injury, illness, or congenital conditions.

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing demand for the cosmetic correction of lower leg deformities resulting from injury, illness, or congenital conditions [1]. The shape of the calf is determined by the development of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles, the length and orientation of the crural bones, and the distribution of subcutaneous fat. To date, calf augmentation for aesthetic purposes is usually achieved by silicone implantation or autologous fat grafting [2], depending on the patient’s needs and anatomical limitations. Options including several types of free flaps using autologous tissue are available, although they are not common. This report describes the use of a free deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap to correct an extensive atrophic scar of the left calf caused by a previous gunshot injury.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old woman presented to the outpatient clinic of the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of our institution with a left calf atrophic scar. She had previously experienced a gunshot wound to her left leg at the age of 11 years, and received debridement, open reduction, internal fixation, and split-thickness skin grafting. This resulted in a depressed and shrunken deformity measuring 18×30 cm on the medial aspect of her lower left leg (Fig. 1). She was a dancer and refused to wear skirts, because she was self-conscious about her disfigured left calf. She desired cosmetic reconstruction to correct the disfigurement. The patient’s right leg was longer than her left leg, and she had osteoarthritis in her left ankle. However, she had no limitation of joint motion caused by scar contracture or other functional problems. She had a fatty abdomen but no other medical problems and was not on any medications. The patient measured 167 cm in height, 74 kg in weight, and had a body mass index of 26.53 kg/m2.

(A) Preoperative view, posterior side of the calf atrophic scar. (B) Preoperative view, medial side of the calf atrophic scar.

The patient was uncomfortable with the idea of using augmentable prosthetics in her body, such as expanders or implants, and favored using her own tissue. In addition, she wanted to correct her fatty abdomen simultaneously, and opted for the correction of both her calf and abdomen in a single-stage operation. After careful consideration, we decided to use a free DIEP flap for calf augmentation, and the patient accepted this plan.

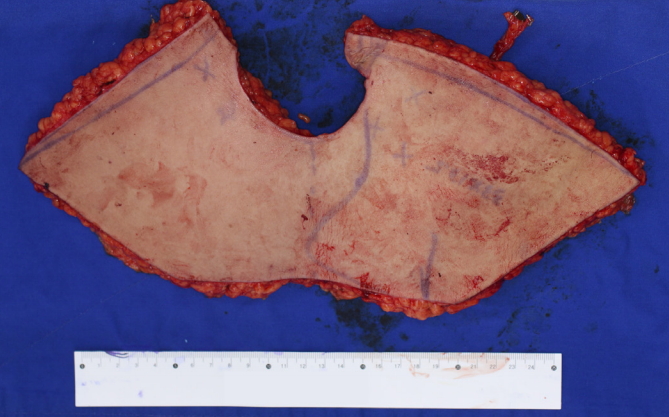

For surgery, the patient was placed in the supine position. Perforator marking was guided by Doppler ultrasonography, and flap design was performed. Segmental occlusion was found in the distal anterior tibial artery and posterior tibial artery due to previous traumatic arterial dissection (Fig. 2). Both inferior epigastric arteries were intact, and no abnormality was detected on abdominal computed tomography angiography. Initially, the scar contracture of the left calf was released. The DIEP flap was elevated, measuring 13.5×33 cm, with an 8-cm inferior epigastric pedicle (Fig. 3). Microvascular end-to-side anastomosis was performed between the inferior epigastric artery and the anterior tibial artery. The inferior epigastric vein was anastomosed to the accompanying vein in an end-to-end fashion. The flap was trimmed to match the left calf and repaired with 4-0 vicryl sutures. The skin edges were closed with 4-0 nylon sutures, and the donor site was covered with local flap advancement. Flap refill was slow, and the pulse was monitored with Doppler ultrasonography immediately postoperatively. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and a refill, color, and Doppler check was done every 2 hours. No postoperative complications occurred during this period. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 8 as the flap appeared healthy, with no congestion, erythema, or necrosis. Debulking of the bulky flap was performed once at 5 months postoperatively (Fig. 4). Currently, the patient is satisfied with the aesthetic and functional outcomes of the calf augmentation.

Using lower-extremity computed tomography angiography, we identified segmental occlusion in the distal anterior tibial artery and the posterior tibial artery with collateral vessels.

DISCUSSION

In our modern lifestyle, there is a considerable emphasis on how we look, with fashion and the media placing a major focus on the contours and shapes of our bodies. Not surprisingly, leg shape has become an increasingly important element of body aesthetics [3], leading to a growing interest in calf augmentation.

Silicone implantation and autologous fat grafting are the most frequently used techniques for calf augmentation. However, silicone implantation is frequently associated with complications, including hyperpigmentation, seromas, extrusion, infection, capsular contracture, removal for cosmetic dissatisfaction, and compartment syndrome [2]. It is also associated with exposure, necrosis of adjacent tissues, and paresthesia due to the compression of peripheral nerves [4]. Autologous fat grafting faces limitations of the quantity of harvestable fat for relatively large defects and the long-term unpredictability of fat volume maintenance [1]. Some have argued that fat grafting also poses a potential risk of fat embolism syndrome, caused by damage to large blood vessels during lipofilling and liposuction procedures [5].

In this case, we first ruled out the use of a silicone implant. Treatment with a silicone implant requires careful dissection in the lower leg to create a pocket for the implant between the investing crural fascia and the gastrocnemius muscle [3]. We would have been unable to create such a pocket, because the subcutaneous tissue, fascia, and muscle were insufficient and there was severe anatomical variation in this case due to the previous gunshot injury (Fig. 5). In addition, the size of the shrunken defect was too large for it to be possible to obtain a sufficient cosmetic effect using fat grafting. Even if autologous fat grafting were possible, the long-term maintenance of the fat volume would be unpredictable. After reviewing the patient’s medical condition and discussing the patient’s needs, we finally concluded that the free DIEP flap was the best choice among the various calf augmentation procedures.

Large skin and subcutaneous defect in the medial aspect of the left lower leg, with extensive calcification, suggestive of a chronic inflammatory lesion. Severe muscle atrophy was also noted.

Free DIEP flap surgery is a useful microsurgical technique for the reconstruction of large defects. The DIEP flap is commonly used for autologous breast reconstructions in breast cancer patients, and also sometimes for patients who require lower extremity reconstruction following trauma. The DIEP flap provides large, 3-dimensional volume enhancement, and the shape and thickness of the flap can be designed to suit defects of various sizes. In addition, because there is relatively minimal donor site morbidity, this type of flap may be a good option for women who have excess abdominal fat, who have already given birth, or who have no future plans to give birth. It provides a cosmetically superior, safe, and sustainable outcome through a single-stage surgical procedure without the need for augmentable prosthetics. Therefore, it can be an ideal alternative to traditional calf-augmentation procedures.

The free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap and the free vertically designed DIEP (VDIEP) flap can also be good alternatives, depending on the situation. The free TRAM flap can achieve a slightly more dramatic increase in calf diameter by contributing muscle bulk. The free VDIEP flap is advantageous in that it does not require relatively excessive tissue dissection, and preserves the possibility of a contralateral flap [6]. It may also be considered as a substitute for the DIEP flap in patients with an abdominal midline scar or a recipient site needing a long and thin flap [6]. However, in our case, we did not need a flap with a volume large enough to require sacrificing the rectus abdominis muscle. Sparing the rectus abdominis muscle leads to less donor site morbidity, such as hernia formation. When a VDIEP flap is used, an abdominoplasty effect on the lower abdomen cannot be obtained, and asymmetric long vertical scars that are difficult to cover with clothing remain in the abdomen. For those reasons, a classic DIEP flap was considered more appropriate than a TRAM flap or VDIEP flap in this case. Flap selection should be based on the patient’s needs and the surgeon’s experience.

The purpose of this paper is to report our experience with successful scar contracture release and calf augmentation using the free DIEP flap. We recommend the free DIEP flap for the correction of large and irregularly shaped atrophic scars of the lower leg caused by injury, illness, or congenital conditions.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

PATIENT CONSENT

The patient provided written consent for the use of her images.