Unilateral pedicled transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap and unilateral free deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap as a surgical alternative in bilateral autologous breast reconstruction

Article information

Abstract

Background

Bilateral microsurgical autologous reconstruction is known to increase operating time, costs, and complications compared to unilateral procedures. This study aimed to determine whether a unilateral pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap and a unilateral deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) free flap could be a feasible option for bilateral reconstruction in selected circumstances.

Methods

A retrospective chart review identified patients who underwent unilateral pedicled TRAM and unilateral DIEP reconstruction for bilateral breast reconstruction between 2011 and 2014. Surgical outcomes, complications, and aesthetic scale questionnaire responses were evaluated.

Results

Fourteen patients were included in this study. Ten patients received bilateral immediate reconstruction, while four patients with a previous history of mastectomy underwent unilateral immediate reconstruction and contralateral delayed reconstruction. All flaps survived without any major complications. A case of nipple-areolar skin necrosis on the pedicled TRAM side and a case of mild abdominal bulging at the free DIEP donor site were reported. There was no partial flap necrosis or palpable fat necrosis. On the aesthetic outcome scale, the free DIEP flaps scored significantly higher than did the pedicled TRAM flaps for overall shape, the upper medial and lower lateral quadrant, and the lateral chest wall.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that a unilateral pedicled TRAM flap together with a unilateral free DIEP flap could be performed as a bridging surgical option as institutions move toward bilateral free-flap reconstructions, as a way to reduce operating time and the risk of microsurgery-related complications with acceptable donor site morbidity and aesthetic outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

The number of patients who consider receiving prophylactic mastectomy has increased concomitantly with the increase in the number of cases of breast cancer; thus, more patients are seeking bilateral breast reconstruction following bilateral mastectomy, although this may not always be medically justifiable [1,2]. In contrast to prosthesis-based reconstruction, the operating time for autologous bilateral reconstructions, especially microsurgical reconstructions, can be significantly longer than that of the corresponding unilateral procedures. Efficiency and safety are both especially important because bilateral reconstruction has been found to increase surgical time, cost, and complications [3,4]. This also applies to bilateral mastectomies [5].

In cases of bilateral free flap breast reconstruction, the use of two co-surgeons not only shortened the overall operating time, but also decreased donor site wound complications [6,7]. However, there may not always be two co-microsurgeons available. We performed co-operations in 14 bilateral abdominally-based reconstructions where one plastic surgeon used a pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap and the other used a deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) free flap. We propose this as a “bridge” procedure for bilateral reconstruction that can provide acceptable donor morbidity, operating time, and microsurgery-related complication risks, while being able to be performed by a single surgeon in hospitals with a lower volume. Based on a detailed comparison of the aesthetic outcomes of each flap through a photograph-based survey, we also discuss the advantages and pitfalls of insetting each hemi-flap.

METHODS

The study was retrospectively approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (2018-1297). Among the 22 female patients who underwent bilateral abdominally-based breast reconstructions immediately following mastectomy on at least one side (immediate breast reconstruction) from March 2011 to March 2014, 14 patients who agreed to undergo reconstruction with one pedicled flap and one free flap were included in this study after they were provided a detailed explanation of the procedure and gave informed consent. A retrospective chart review based on a prospectively-maintained database was performed to evaluate operative details and surgical outcomes, including any complications.

Preoperative computed tomographic angiography confirmed patent superior and deep inferior epigastric arteries in all patients. All reconstructions, pedicled or free, were based on an ipsilateral pedicle. If a delayed reconstruction was performed on one side (n=4), a pedicled TRAM flap was used for the delayed side to facilitate the 2-team approach. If a nipple-areolar complex (NAC) could not be spared (n=2), a free DIEP flap was performed on that side to help monitor the flap.

Flap elevation and transfer were performed in the usual manner. Internal mammary vessels were always used as recipients for free flaps. Two flaps were placed horizontally upside down, setting zone III at the medial side of the defect to maximize lower-lateral fullness. Symmetry was confirmed in the sitting position. No venous coupler or synthetic mesh was used in any case.

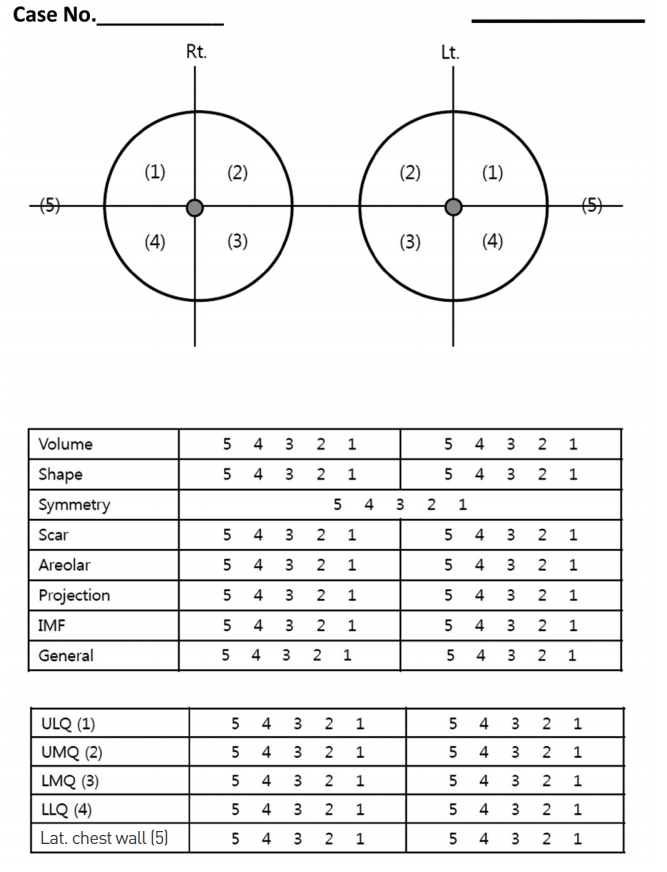

The aesthetic evaluation was based on the aesthetic items scale developed by Dikmans et al. [8] and Visser et al. [9] with some modifications. Clinical photographs were available for 10 patients who did not receive any secondary procedures after NAC reconstruction was completed. Five standardized photographs, including a frontal view, each lateral view, and each 45° angle were presented to 10 plastic surgeons and 10 laymen who were blind to the study design. They completed the aesthetic items scale, including overall symmetry; scarring; the NAC; the size, shape, projection, and inframammary fold (IMF) of each breast; and satisfaction with each of the 4 quadrants of the breast mound and lateral chest wall (Fig. 1). A 5-point Likert scale was used for measurements, with scores ranging from 5 (strongly favorable) to 1 (strongly unfavorable). The scores for each item were compared between the free DIEP flaps and pedicled TRAM flaps using the paired t-test. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Modified aesthetic items scale questionnaire. The questionnaire asked about overall symmetry; scarring; the nipple-areolar complex; the size, shape, projection, and inframammary fold (IMF) of each breast; and satisfaction with each of the four quadrants of the breast mound and lateral chest wall, using a 5-point Likert scale. ULQ, upper lateral quadrant; UMQ, upper medial quadrant; LMQ, lower medial quadrant; LLQ, lower lateral quadrant; Lat., lateral.

RESULTS

The average age of the patients was 41.4 years (range, 34–52 years), and their average body mass index (BMI) was 22.7 kg/m2 (range, 19.5–30.5 kg/m2). No patient had diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or a history of smoking. Nine cases were therapeutic because of bilateral breast cancer (either ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive ductal carcinoma), one was risk-reducing, and four patients had unilateral breast cancer with a previous history of modified radical mastectomy on the other side. One patient had a history of previous radiation after breast-conserving surgery and two had undergone adjuvant radiation after reconstruction. All two adjuvant radiation therapy cases were bilateral immediate reconstructions, and radiotherapy was performed on the free flap side. The patients were followed up for a median of 5 years.

Regarding the free DIEP side (all immediate reconstructions), the average weight of the mastectomy specimen was 294.8 g (range, 159–424 g) and the average weight of the free flap was 295.5 g (range, 151–507 g), with a mean flap-to-specimen weight ratio of 1.16.

All flaps survived without any major complications. No systemic complications, such as systemic infection and cardiovascular or pulmonary events, were reported. A case of nipple-areolar skin necrosis on the pedicled TRAM side and another case of lower abdominal bulging without a true hernia on the free DIEP donor site were reported. There were no cases of partial flap necrosis or palpable fat necrosis. On average, the patients received nipple reconstruction at 8.4 months and areolar tattooing at 12.7 months after reconstruction surgery.

Regarding the aesthetic comparisons, the scars and NAC were excluded because they were greatly influenced by the mastectomy procedure used. Of the 10 cases available for clinical photograph analysis, three delayed- and immediate-reconstruction cases were later excluded because the overall questionnaire results were significantly skewed to the delayed reconstruction side. Overall, the free DIEP flap side received higher aesthetic scores except for projection. However, the difference was significant only for the overall shape, upper medial and lower lateral quadrants, and lateral chest wall (Table 1).

Case 1

A 35-year-old female patient with a BMI of 24 kg/m2 presented with bilateral palpable breast nodules that were diagnosed as invasive ductal carcinoma by biopsy. Breast surgeons initially recommended breast-conserving surgery, but the patient wanted the whole breast resected. Bilateral nipple-areolar skin sparing mastectomy (220 g each) followed by a pedicled TRAM flap on the right side and a free DIEP flap (400 g) on the left side were performed. No postoperative adverse events were reported. She underwent adjuvant chemotherapy. We recommended liposuction on her flank and monitoring flap excision, but the patient did not want any secondary procedures (Fig. 2).

Five standardized photographs of the patient in case 1 taken 15 months postoperatively. A 35-year-old female patient underwent bilateral nipple-areolar skin-sparing mastectomy followed by right pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous and left free deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap reconstruction. She did not want any secondary procedures. (A) Right oblique view, (B) right lateral view, (C) frontal view, (D) left oblique view, and (E) left lateral view.

Case 2

A 37-year-old female patient with a BMI of 21.3 kg/m2 was diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer at an annual examination. She had a ductal carcinoma in situ in her right breast and invasive ductal carcinoma in her left breast. Since the right mass was adjacent to the nipple, the surgical plan was skin-sparing mastectomy with a free DIEP flap (240 g) on her right side (mastectomy specimen weight: 337 g) and nipple-sparing mastectomy with a pedicled TRAM flap on her left side (mastectomy specimen weight: 273 g). After 6 months, the patient received nipple sharing on her right breast with harvesting from the left nipple, and underwent tattooing after another 6 months (Fig. 3).

Five standardized photographs of the patient in case 2 taken 12 months after the completion of reconstruction. A 37-year-old female patient underwent right skin-sparing mastectomy with a free deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap and left nipple-areolar skin-sparing mastectomy with a pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. After 6 months, the patient received nipple sharing on her right breast with harvesting from the left nipple, and underwent tattooing after another 6 months. (A) Right oblique view, (B) right lateral view, (C) frontal view, (D) left oblique view, and (E) left lateral view.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that bilateral DIEP free flap breast reconstruction was associated with increased rates of complications and total flap loss when compared with the corresponding unilateral procedures [3,4]. However, Beugels et al. [10] claimed that there were no significant differences regarding major flap complications between unilateral and bilateral free DIEP reconstructions, although it should be noted that a venous coupler was more frequently used in bilateral reconstructions. It might simply be the case that bilateral reconstruction doubles the incidence of complications, but the increased complication rate might also be meaningfully associated with the elongated operating time and difficulty of the operation. Wade et al. [4] reported that although both unilateral and bilateral DIEP breast reconstructions were safe and had a low risk of complications, it was true that postoperative complications requiring reoperation were twice as common and the risk of total flap loss was six times greater in bilateral reconstructions. They explained that bilateral reconstruction precluded the surgeon from choosing a more favorable side perforator or utilizing the contralateral side to replace or rescue a failing unilateral flap [3].

Systemic backup and hospital volume are other important factors that should be considered when interpreting the literature regarding outcomes of bilateral free flap reconstructions [11,12]. An adjusted analysis by Tuggle et al. [11] revealed that high-volume hospitals were associated with a decreased likelihood of microvascular complications, procedure-related complications, and total complications. However, this should not be interpreted as an absolute guideline because there are hospitals with a few experienced surgeons and an overall lower volume per year and hospitals with a larger number of less-experienced surgeons and a greater overall annual case volume [11].

The average operating time for bilateral mastectomy followed by immediate reconstruction was 735 minutes (range, 655–824 minutes) in this study of cases performed between 2011 and 2014. The average operating time for bilateral immediate free flap reconstructions during the same period (n=8) was 902 minutes (range, 811–1,015 minutes). It should be noted that the case series presented herein dates to 4 to 7 years ago, and it now takes approximately 640 minutes on average at our center for bilateral mastectomy and immediate bilateral free flap reconstruction. Canizares et al. [12] showed that the average length of surgery for bilateral DIEP flaps could be shortened to 346 minutes when surgical efficiency was optimized by multiple efforts such as preoperative planning with computed tomography and magnetic resonance angiography, a stable dedicated operating room team (two microsurgeons, a trained certified registered nurse and circulating nurse, an anesthesiologist, and a scrub technician) for the entire procedure, and a systematic approach for surgery.

The average flap-to-breast weight ratio was 1.16 (range, 0.60–1.80) in our results, and the flap weight was generally enough to compensate for the previous breast tissue. However, the results for aesthetic outcomes were somewhat disappointing. All aesthetic scales failed to reach 4 out of 5. The scores for shape were significantly lower for the pedicled flap side, although the volume, projection, IMF, and overall aesthetic results were similar for both flaps. The differences were significant for the medial quadrant, and especially for the lower lateral quadrant and lateral chest wall. We explain this result in terms of the lack of “dimension” of the flap. Although hemi-flap breast reconstruction would always be suitable for this issue, the need to place part of the skin paddle on top of the muscle further aggravates this problem, as shown in our results. Blondeel et al. [13] proposed inspirational and practical guidelines for shaping the breast with a DIEP flap for unilateral reconstruction, according to which lateral fullness can be obtained by lateral shifting of the flap, and projection of the mound can be guaranteed by bunching of the skin paddle, both of which are difficult to fully accomplish using a hemi-flap.

Injudicious extension of the flap should be avoided, however, because doing so might lead to increased donor site wound problems and fat necrosis in zone III. McAllister et al. [14] reported an incidence of donor site wound dehiscence as high as 41% in their earlier experience of bilateral breast reconstruction with abdominal free flaps. It was reported that the incidence of fat necrosis in bilateral free flap reconstruction was significantly lower than in unilateral reconstruction because use of zone II was precluded from the beginning [10]. However, the use of medial row perforators in bilateral free flap breast reconstruction increased the incidence of fat necrosis in zone III [15], and the increased weight ratio of the inset flap to the harvested flap was associated with increased fat necrosis in zone III [16].

Recent studies regarding donor site function after abdominally-based breast reconstruction have mostly focused on comparing free muscle-sparing TRAM flaps and DIEP flaps, but the results are not yet conclusive. Seidenstuecker et al. [17] asserted that patients who underwent breast reconstruction with a DIEP flap had significantly better muscle function, as assessed by myosonographic examinations, at 6 months postoperatively than patients who underwent a muscle-sparing free TRAM flap and that good preoperative muscle function favored the use of a DIEP flap for breast reconstruction. In contrast, Uda et al. [18] reported that abdominal muscle function measured by isokinetic dynamometry recovered to preoperative levels in both groups at 6 months postoperatively. Furthermore, Alderman et al. [19] in 2006 claimed that breast cancer patients who received TRAM reconstructions had a ≤20% long-term deficit in trunk flexion peak torque as measured with Cybex machines and that there was no significant difference in trunk function between patients receiving pedicle and free TRAM reconstructions at 2 years postoperatively. Our study did not focus on muscle function evaluation after bilateral pedicled TRAM and DIEP flap reconstruction. However, the patients stated that they had no functional deficit in daily activities or usual exercises in general at 1 year postoperatively and beyond. Although it is true that the DIEP flap would be an ideal method regarding donor site morbidity, the pedicled TRAM flap is still a viable option when the total reconstructive cost (both reimbursement and expenses) and overall postoperative morbidity, including the possibilities of reoperation and vascular compromise, are taken into consideration, as shown in analyses comparing pedicled and free flaps [20,21].

A major limitation of this study is that we only compared the use of two types of flaps as separate hemi-flaps in individual patients for the aesthetic analysis, so our results cannot be used to compare the aesthetic outcomes of unilateral pedicled flaps and unilateral free flaps, which constitute the majority of breast reconstructions. However, we believe that our results provide important insights for the insetting and shaping procedure when a patient needs bilateral reconstruction separately or unilateral reconstruction with a hemi-flap because of the abdominal midline scar.

Another issue is that the number of cases was too small to draw conclusions about complication rates or donor site function after this procedure. A comparison of the results with those of bilateral pedicled flaps or bilateral free flaps is lacking. We admit that this procedure likely had higher donor site morbidity than bilateral DIEP flap reconstruction. We also agree that comparing surgical/aesthetic outcomes, as well as procedure-related resource use, between bilateral pedicled TRAM flap and bilateral free DIEP flap reconstruction would have been more useful for research and clinical reference.

We followed up 14 selected patients who received unilateral pedicled TRAM and unilateral free flap surgery. Roslan et al. [22] reported a case similar to those in our series and found that this procedure had acceptable donor and recipient site morbidity. We do not argue that this procedure is optimal. Instead, we would like to propose this surgery as a kind of bridging procedure when an institution is beginning to perform an increasing number of bilateral autologous reconstructions. The judicious application of this technique could contribute not only to reducing the microsurgeon’s fatigue, operating time, and the incidence of microsurgery-related complications, but also to decreasing the total reconstruction cost and length of hospitalization in centers with fewer microsurgeons and limited resources readily available.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 2018-1297) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

PATIENT CONSENT

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of their images.