|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 28(1); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

A recent concern in breast reconstruction procedures is skin color mismatch of the pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap. With the goal of objectively quantifying the skin tone of the TRAM flap donor site, contralateral breast, and flap, a comparative study was conducted.

Methods

This study was conducted in July 2021, included 17 patients who received delayed breast reconstruction via TRAM flaps from January 2016 to December 2020 with at least 12 months of follow-up. Melanin levels and redness values of the flap, abdomen, and contralateral breast were measured in patients using a skin pigmentation analyzer. Furthermore, in 20 healthy women in their 40s to 60s, measurements were made of the abdomen, as well as breast.

Results

The contralateral breast had lower mean melanin and redness than the abdomen. The flaps had slightly higher melanin levels than the contralateral breasts. The flaps tended to have higher redness values, but the difference was not significant. The difference between the flap and abdomen was significant for melanin, but not redness. Preoperative radiotherapy did not affect skin tone. The upper abdomen showed lower melanin and redness than the lower abdomen.

Conclusions

The breast had a brighter skin tone than the abdomen. The upper abdomen showed brighter skin tone than the lower abdomen, and the area used as the donor site of the TRAM flap presented the same tendency. In the process of TRAM flap engrafting, the melanin level of the tissue decreases, and the redness value tends to increase slightly compared to the contralateral breast.

Breast cancer is the second most common type of cancer worldwide [1]. There are 1.7 million new cases annually, and the number is increasing every year [1]. The mortality of breast cancer has decreased due to advances in diagnosis and treatment techniques. However, this has made cosmetic problems more prominent. Therefore, for the emotional stability and aesthetic satisfaction of patients, breast reconstruction has become a necessity rather than an option.

The pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap is a technique using the superior epigastric vessel as the main pedicle. The TRAM flap is widely used as an option for autologous breast reconstruction [2]. It is the most reliable option when a donor vessel cannot be detected around the breast due to radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy [3]. However, one of the disadvantages of the TRAM flap is the color mismatch between the existing breast skin and the donor site skin [4]. A mismatch of skin tone with the contralateral breast can cause dissatisfaction and stress for patients.

Therefore, with the goal of objectively quantifying patients’ subjective judgments, we compared the skin tones of the contralateral breast, donor site (abdomen), and flap using quantitative and objective measurements.

A single-center study was conducted on 17 of 32 patients who received a pedicled TRAM flap for delayed breast reconstruction from January 2016 to December 2020. All participants were recruited as patients 12 months or more after TRAM surgery. All measurements were performed in July 2021, and the follow-up period was determined relative to that month. Information was gathered from medical records about age, body mass index (BMI), underlying disease, smoking, alcohol intake, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, and other surgery than breast reconstruction, patients who underwent radiotherapy after breast reconstruction, patients who had bilateral breast cancer or skin diseases, and patients who had not completed wound healing were excluded from the study.

In the patient group, the skin tone of the lower abdominal area harvested during the TRAM flap could not be measured. To supplement this shortcoming, 20 healthy women in their 40s and 60s were recruited and their skin tone and hydration were measured on the breast and abdomen.

Measurements were made on the contralateral breast, donor site (abdomen), and recipient site (TRAM flap) of each patient using a skin pigmentation analyzer (SPA99; Courage+Khazaka Electronics, Köln, Germany) and skin diagnostic device (SD202; Courage+ Khazaka Electronics). Melanin levels and redness values composing skin tone were measured using a SPA99 (Fig. 1). The measurement scale ranges from 0 to 99. The closer a score is to 0, the brighter the skin is, and the closer the score is to 99, the darker the skin is.

Skin vascularity depends on the environment or the patient’s condition and impacts the skin tone. Therefore, external variables were controlled by conducting the study under constant conditions to the extent possible. The room temperature was kept constant at 26°C using an air-conditioner. All patients rested for at least 15 minutes before the measurements, and the axillary temperature was checked. The measurements were consistently made with the patient in the supine position. The same person measured all the patients to minimize error due to the operator-dependence of the method.

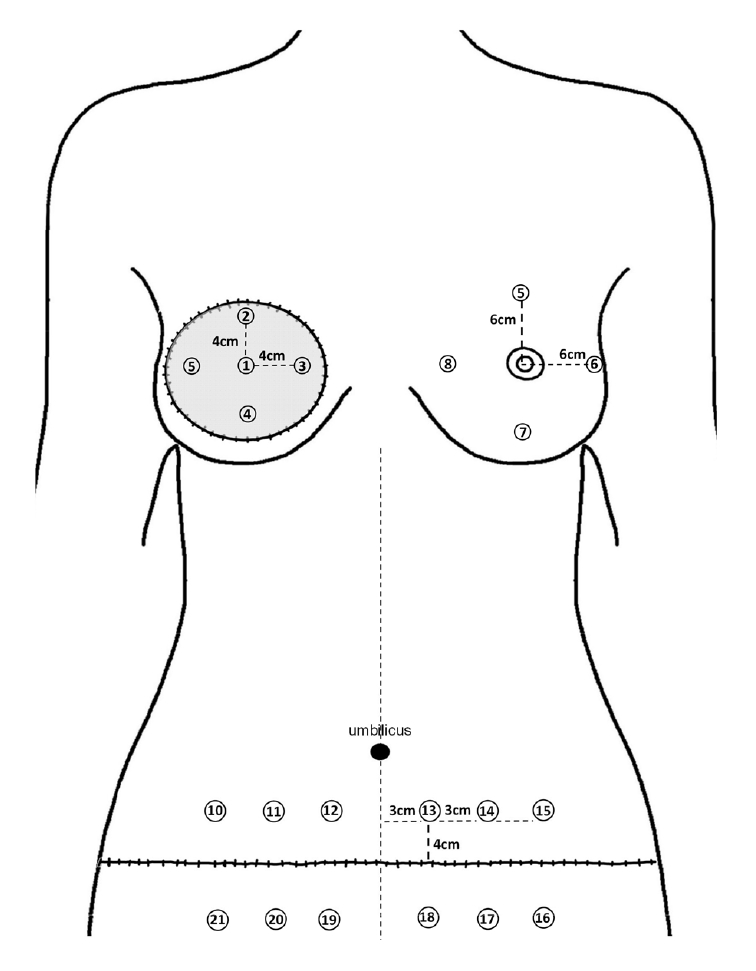

In patients with breast cancer, the contralateral breast skin unaffected by treatment was measured. Since the skin tone may not be the same across the entire breast, measurements were performed at four locations 6 cm apart from the nipple-areolar complex (Fig. 2). The average values of four sites were set as the skin tone data.

When measuring the donor site, hyperpigmentation and dyspigmentation can be observed in the periphery of the scar due to contracture. To minimize the resulting error, the measurements were made as follows. Distances of 3, 6, and 9 cm were marked from the point where the vertical midline and the lower abdominal scar met on both sides. Measurements were performed at a point 4 cm vertically from the markings, and the average melanin level and redness value measured there were recorded as the skin tone data for the lower abdomen (Fig. 2). In addition, the abdomen was divided into two portions—the upper (measurement points 10-15) and lower (measurement points 16-21)—and the average value of skin tone was recorded for each part.

The center of the TRAM flap skin was set at the midpoint of the long axis of the flap. Measurements were taken at five locations, including the central point and four points that were 4 cm apart from the central point (Fig. 2). The average melanin level and redness value at these five points were recorded as the skin tone data.

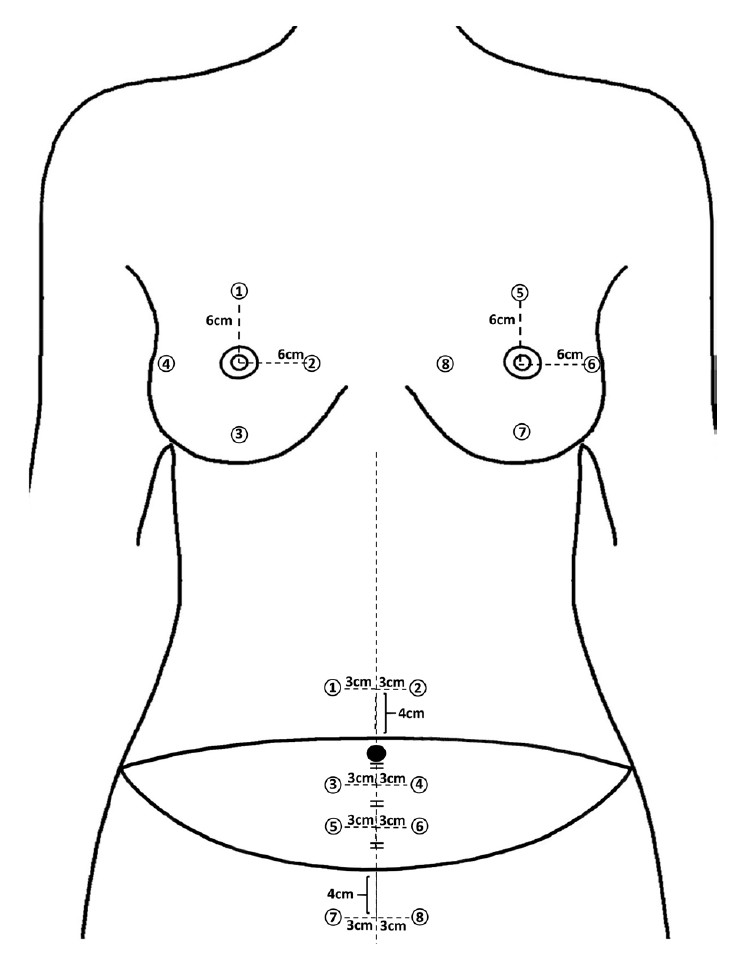

The breast measurements were made at the same points as in the post-TRAM patients (Fig. 3). The average values of melanin and redness measured at eight sites were used as the skin tone data.

Abdominal skin tones were measured at eight sites (Fig. 3). Points 1 and 2 were classified as the upper abdomen, points 3, 4, 5, and 6 as the flap, and points 7 and 8 as the lower abdomen. Furthermore, points 3 and 4 were subdivided into the upper flap and points 5 and 6 as the lower flap.

The measurement standard was set based on a conventional TRAM flap design. The TRAM flap was designed on a healthy woman’s abdomen. Then, two points 4 cm upward and 3 cm horizontally apart from the midpoint of the upper flap margin were defined as points 1 and 2. Likewise, two points located 4 cm downward and 3 cm horizontally on both sides from the midpoint of the lower flap margin were defined as points 7 and 8. This was done to measure the upper and lower parts, consistent with the abdomen measurement criteria in the patient group. The points where the short axis of the flap is divided into three parts and a 3-cm distance from the 1/3 and 2/3 points horizontally to both sides were defined as points 3, 4, 5, and 6 (Fig. 3), respectively.

For most variables in this study, mean values were compared using the Mann-Whitney test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test because the sample size was small. The Bonferroni correction was used to reduce the errors arising from multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The general characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. All patients had previously received delayed breast reconstruction. The average age of the participants was 56.35 years, and their average BMI was 24.51 kg/m2. The numbers of patients who smoked and consumed alcohol were one (5.9%) and two (11.8%), respectively. Of the 17 patients, five (29.4%) had undergone radiotherapy, 13(76.5%) had undergone chemotherapy, and seven (41.2%) had received hormone therapy. Most of the participants in the study were multiparous, and 94.1% of the patients were postmenopausal. In addition, 70.6% of the patients had previously undergone other surgical procedures causing an abdominal scar (cesarean section, open laparotomy, etc.) The average follow-up period of the participants was more than 30 months, and the minimum period was 14 months. The follow-up period was defined as the number of months after surgery at the time this study was conducted (July 2021).

As shown in Table 2, the mean age of healthy women participating in the study was 56.55 years, and their average BMI was 24.97 kg/m2. Table 3 presents data on the mean values and ranges of melanin, erythema, and hydration of the flaps, breasts, and abdomen measured in the patient group. Table 4 also shows data for breast and abdomen measurements obtained in healthy women.

Comparison of melanin levels and redness values between the donor site, flap, and contralateral breast. As shown in Table 5, the melanin level in flaps was 22.56 ± 4.30, and redness was 36.08 ± 5.75. In contralateral breasts, the melanin level was 22.46 ± 4.06 and redness was 33.91 ± 4.56. At the donor site, the melanin level was 26.99± 4.67 and redness was 38.14 ± 5.16.

First, the difference in melanin levels between the flaps and contralateral breasts was non-significant. The redness values showed a slight difference in numerical terms, but it was not statistically significant (P = 0.102). In the comparative analysis between the flaps and donor site, the melanin level showed a difference in the average of 4.43, while the difference in the average redness value was 2.06; however, the difference was only significant for melanin levels(melanin: P < 0.001, redness: P = 0.076). A significant difference was observed in both melanin and redness between the contralateral breasts and donor site (melanin: P < 0.001, redness: P = 0.002).

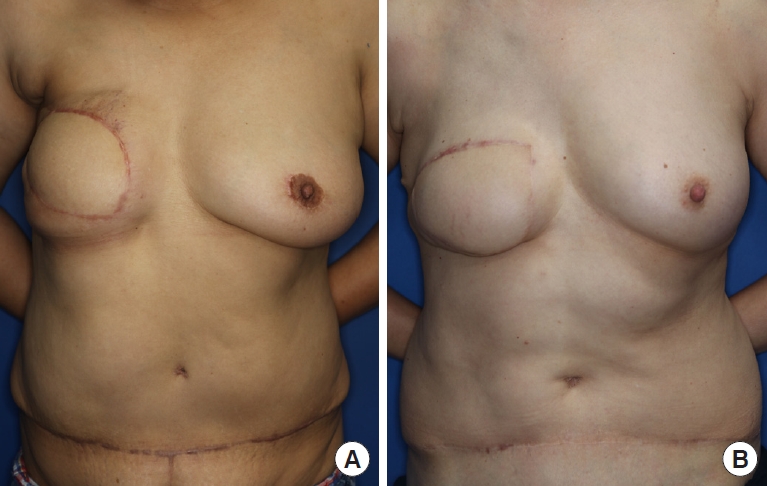

The non-radiotherapy group tended to have lower melanin levels and higher redness values than the radiotherapy group, but this difference was not significant (Table 6). The average melanin level of the flap in the non-radiotherapy group was 21.92 ± 4.26, while that in the radiotherapy group was 24.12 ± 4.46. In contrast, the mean redness value of the flaps was 36.75 ± 6.63 in the non-radiotherapy group and 34.48 ± 2.55 in the radiotherapy group. Fig. 4 presents some cases of patients who did or did not receive radiotherapy.

In Table 7, the average melanin level of the flaps was 22.56 ± 4.30 and the redness value was 36.08 ± 5.75. The average melanin level of the upper portion was 25.19 ± 4.81 and the average redness value was 37.56 ± 3.89. The difference in the upper portion values was 2.63 for melanin and 1.48 for redness. Of these, only the difference in melanin levels was statistically significant (P = 0.002). When the upper and lower portion were compared, the lower portion had higher values, with differences of 3.59 for melanin and 1.16 for redness value between the two groups. Likewise, only the difference in melanin levels was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 8 shows that the contralateral breasts and the upper portion of the donor site showed statistically significant differences in both melanin levels and redness values, as was also the case for differences between the contralateral breast and lower portion of the donor site.

Table 9 shows data comparing skin tone by abdominal area in healthy middle-aged women. The melanin levels showed statistically significant differences between all three segments of the abdomen (upper: 23.83 ± 4.63, flap: 29.00 ± 5.38, lower: 30.43 ± 4.43). The redness values showed statistically significant differences in all three groups, except for the difference between the flap sites and the lower abdomen (upper: 35.98 ± 1.47, flap: 40.29 ± 1.60, lower: 40.28 ± 2.67).

Table 10 shows the results of comparative analyses of differences between the breast and flap sites (upper and lower flap) groups in healthy women. Statistically significant differences were found in melanin levels (breast: 23.44 ± 3.21, upper flap: 26.65 ± 4.81, lower flap: 31.35 ± 6.00), and redness values (breast: 33.94 ± 2.53, upper flap: 38.83 ± 2.91, lower flap: 41.75 ± 2.37) between the three groups.

Numerous studies on breast reconstruction have been published, but most have tended to focus only on volume symmetry and cosmetic outcomes while wearing outerwear [6,7]. However, as increasingly many patients pay attention not only to volume symmetry, but also to whether skin tone is well matched, it is necessary to pay sufficient attention to skin color symmetry. Even in the same person, the skin tone varies across body parts. The medial arm is the lightest, and the forehead and scapula areas are the darkest [8]. In this study, a comparative analysis was conducted using instruments that can measure melanin and redness, two of the most important factors that determine skin tone.

In this study, both the melanin and redness levels of the TRAM flaps were higher than those of the contralateral breast. The abdomen showed higher melanin and redness than the flap. To summarize this, when a TRAM flap is performed, the donor tissue is inset and engrafted to the recipient site, and the original melanin level is reduced. Through these processes, the melanin level of the flap and contralateral breast tend to become similar to each other. The redness value of the donor site decreases after being set in the recipient site. However, it tends to be higher than that of the contralateral breast.

It is not clear why the skin tone changed after abdominal tissue was transferred to the breast through TRAM flap surgery. It is likely that the skin in flaps had lower melanocyte function than normal, undamaged skin. One possible explanation relates to the fact that melanocytes are confined to the human epidermis; therefore, when an incision is made for the flap, transient relative ischemia and hypothermia damage melanocytes [9,10]. This may be a reason why the flap melanin levels were observed to be lower than those of abdominal skin.

Regarding redness values, the flap may have increased vascularity compared to contralateral breast tissue due to the activation of collateral circulation and the occurrence of neovascularization during the flap engraftment process [11]. This may explain why the redness value of the flaps was higher than that of the contralateral breasts.

As a result of comparing the effect of radiation on skin tone, no significant difference in melanin and redness levels was found. Preoperative radiotherapy contributes to a poor prognosis, by increased rates of complications and morbidity [12]. However, the results of this study showed that preoperative radiotherapy was not related to the skin tone of the TRAM flap.

In healthy women, significant differences were found in melanin level and redness value in each group, except for redness values of the flap and lower abdomen. Through this, it could be inferred that there was a difference in skin tone even within the abdominal area, and that the upper abdomen had a brighter skin tone than the lower abdomen. With this trend, the upper flap had a lighter skin tone than the lower flap.

Because the pedicled TRAM flap uses the superior epigastric artery as the pedicle, it is most often rotated 180° and set in the breast [3]. Therefore, if the flap is designed to include as much of the skin of the upper portion as possible, skin tone mismatching can be reduced. Furthermore, this type of design will be advantageous for flap survival since the upper portion skin of the abdomen is closer to the area predominantly supplied by the superior epigastric vessel.

In this study, all cases involved delayed reconstruction, and the TRAM flap was performed mostly with the contralateral rectus abdominis as the pedicle. In accordance with this, the authors extensively considered the strategy of using the upper portion of the lower abdomen as the donor site. First, after donor site skin incision, dissection of the upper flap is carried out obliquely in the cephalic direction to secure as much soft tissue as possible. In particular, care must be taken to minimize soft tissue damage when dealing with the contralateral side of the upper flap. Second, precise umbilical incision and dissection ensure that the donor’s upper portion is not damaged. Third, the lower incision line should be as low as possible within the limit of primary closure without tension so that the scar can be covered by the bikini line.

A limitation of this study is that the number of participants was small. Although the Bonferroni correction was applied to supplement the small population, the reliability of the statistical analysis may nevertheless be low. Further large-scale studies are needed to determine whether the skin tone value of the area used as the TRAM flap and its periphery is consistent. Another problem relates to the consistency of the skin tone measuring device. A disadvantage of this device is that melanin levels and redness values change depending on the pressure applied to the probe tip by the measurer. An effort was made to minimize this error by having one measurer make several measurements while attempting to apply the same pressure, but variation due to inconsistencies in the applied pressure cannot be completely ruled out.

In conclusion, melanin levels were similar in contralateral breasts and TRAM flaps, but redness values tended to be higher in TRAM flaps than in contralateral breasts. Therefore, the subjective complaint of breast color mismatch in patients who received a TRAM flap may be due to the difference in redness values. Breast skin was generally brighter than abdominal skin. The skin in the upper portion of the abdomen generally was brighter than the skin in the lower portion. When performing a TRAM flap, referring to these findings will have a positive effect on improving the patient’s breast color asymmetry.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Sam Yong Lee is an editorial board member of the journal but was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chonnam National University Hospital (IRB No. CNUH-2021-255) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of their images.

Fig. 1.

Measurement devices. (A) Skin pigmentation analyzer (SPA99, Courage+Khazaka Electronics). This device was used to measure the melanin levels and redness values of skin. (B) Skin diagnostic device (SD 202, Courage+Khazaka Electronics). This tool was used to measure skin hydration.

Fig. 2.

The points where skin tone was measured in this study (posttransverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous patients). In the contralateral breast, measurements were performed at four locations 6 cm apart from the nipple-areolar complex. In the donor site (abdomen), distances of 3 cm, 6 cm, and 9 cm from the midline were marked on both sides. Measurements were performed at a point 4 cm vertically upward and downward from the mark. The recipient site (flap) was measured at five locations: the central point and four points that were 4 cm apart from the center.

Fig. 3.

The points where skin tone was measured in this study (in healthy middle-aged women). The breast was measured according to the same criteria as in Fig. 2. First, the transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap was designed on the healthy women’s lower abdomen. Points 1 and 2 were defined as two points located 4 cm vertically upward and 3 cm horizontally away on each side from the midpoint of the upper flap margin. Points 7 and 8 were defined as two points located 4 cm vertically downward and 3 cm horizontally away on each side from the midpoint of the lower flap margin. After marking the point that divides the short axis of the flap into thirds, points 3, 4, 5, and 6 were defined as points 3 cm horizontally apart from the 1/3 and 2/3 points, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Comparison between two cases, with or without preoperative radiotherapy. (A) A 56-year-old patient who underwent preoperative radiotherapy (15 months after a TRAM flap and contralateral breast mastopexy). After conventional mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy were performed. Pigmentation and low skin quality were observed in the upper margin of the flap due to radiation. (B) A 59-year-old patient who did not undergo preoperative radiotherapy (27 months after TRAM flap). After conventional mastectomy, chemotherapy and hormonal therapy were performed. Compared to case (A), the postoperative scar of the flap margin was less conspicuous. TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous.

Table 1.

Participants’ baseline characteristics in the group of breast cancer patients

Table 2.

Participants’ baseline characteristics in the group of healthy women

| Characteristics | Value (n = 20) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 56.55 ± 4.51 (47–63) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.97 ± 1.54 (22.03–28.30) |

| History of previous abdominal surgery | 10 (50.0) |

Table 3.

Measured values of areas of interest in the breast cancer patients

Table 4.

Measured values of areas of interest in the healthy women

Table 5.

Comparison of melanin and redness values between areas of interest in breast cancer patients

| Flap | Contralateral | Abdomen | P-valuea) (flap vs. contralateral) | P-valuea) (flap vs. abdomen) | P-valuea) (contralateral vs. abdomen) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanin | 22.56 ± 4.30 | 22.46 ± 4.06 | 26.99 ± 4.67 | 0.962 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Redness (erythema) | 36.08 ± 5.75 | 33.91 ± 4.56 | 38.14 ± 5.16 | 0.102 | 0.076 | 0.002 |

Table 6.

Comparison of flap melanin and redness according to whether patients had received preoperative radiotherapy

| No radiotherapy (n=12) | Radiotherapy (n=5) | P-valuea) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanin | 21.92 ± 4.26 | 24.12 ± 4.46 | 0.352 |

| Redness (erythema) | 36.75 ± 6.63 | 34.48 ± 2.55 | 0.292 |

Table 7.

Comparison of melanin and redness between the flap and upper and lower portion of the abdomen in the breast cancer patients

| Flap | Upper portion | Lower portion | P-valuea) (flap vs. upper) | P-valuea) (flap vs. lower) | P-valuea) (upper vs. lower) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanin | 22.56 ± 4.30 | 25.19 ± 4.81 | 28.78 ± 4.80 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Redness (erythema) | 36.08 ± 5.75 | 37.56 ± 3.89 | 38.72 ± 6.62 | 0.130 | 0.037 | 0.124 |

Table 8.

Comparison of melanin and redness between the contralateral breast, upper and lower portion of the abdomen in the breast cancer patients

| P-valuea) (contralateral breast vs. upper portion) | P-valuea) (contralateral breast vs. lower portion) | |

|---|---|---|

| Melanin | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Redness (erythema) | 0.004 | 0.005 |

Table 9.

Comparison of melanin and redness values between areas of the abdomen in healthy women

| P-valuea) (flap vs. upper) | P-valuea) (flap vs. lower) | P-valuea) (upper vs. lower) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanin | < 0.001 | 0.003 | < 0.001 |

| Redness (erythema) | < 0.001 | 0.808 | < 0.001 |

REFERENCES

1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359-86.

2. Myers PL, Nelson JA, Allen RJ Jr. Alternative flaps in autologous breast reconstruction. Gland Surg 2021;10:444-59.

3. Wu JD, Huang WH, Qiu SQ, et al. Breast reconstruction with single-pedicle TRAM flap in breast cancer patients with low midline abdominal scar. Sci Rep 2016;6:29580.

4. Gherardini G, Thomas R, Basoccu G, et al. Immediate breast reconstruction with the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap after skin-sparing mastectomy. Int Surg 2001;86:246-51.

5. Amano K, Xiao K, Wuerger S, et al. A colorimetric comparison of sunless with natural skin tan. PLoS One 2020;15:e0233816.

6. Lee TJ, Cho JM, Jo T, et al. Volumetric changes of the pedicled transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap and the contralateral native breast during long-term follow-up. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2019;25:95-102.

7. Yoon JS, Oh J, Chung MS, et al. The island-type pedicled TRAM flap: improvement of the aesthetic outcomes of breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2020;73:1060-7.

8. Han K, Choi T, Son D. Skin color of Koreans: statistical evaluation of affecting factors. Skin Res Technol 2006;12:170-7.

9. Castellano-Pellicena I, Morrison CG, Bell M, et al. Melanin distribution in human skin: influence of cytoskeletal, polarity, and centrosome-related machinery of Stratum basale keratinocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:3143.

10. Prohaska J, Jan AH. Cryotherapy. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Aug [cited 2021 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482319.

11. Lucas JB. The physiology and biomechanics of skin flaps. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2017;25:303-11.

12. Long JN, McCraw JB, Vasconez LO, et al. Breast reconstruction following mastectomy. In: Bland KI, Copeland EM, editors. The breast: comprehensive management of benign and malignant diseases. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Walter Burns Saunders; 2009. p. 839-75.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 2,629 View

- 191 Download

- Related articles in AAPS

-

Delivery technique for the pedicled transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap2022 October;28(4)