|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 28(4); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

The practice of medicine by uncertified personnel is a common concern in public healthcare. Although the introduction of the Korean National Health Insurance Service has significantly reduced the number of these cases, the problem persists in the field of aesthetics. Herein, we report an outbreak of devastating facial stigmata in patients treated with illegal cosmetic procedures.

Methods

During 1 week in November 2021, five patients presented to Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital for the management of identical patterns of severe facial scarring. Each patient had been treated for “skin rejuvenation” by a single unlicensed practitioner. Months of needling therapy by the practitioner, aimed at resolving the problem, only aggravated the scarring. The victims visited our hospital after the practitioner ceased to answer their calls. The patients had similar presentations with multiple prominent scars on both cheeks. Ectropion of the right lower eyelid due to scar contracture was observed in one patient.

Results

Five monthly treatments with intralesional triamcinolone injection and laser therapy were performed. Despite thorough management, the patients were left with improved but distinctive stigmata on their faces.

Conclusions

Cases of illegal aesthetic procedures are difficult to prosecute because the patients have implicitly agreed to the procedure. Therefore, active legislative measures should be adopted to prevent further victimization. Public education on the dangers of illegal aesthetic practices is also necessary.

The definition of cosmetic (aesthetic) practice is somewhat subjective. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, “cosmetic plastic surgery includes surgical and nonsurgical procedures that enhance and reshape structures of the body to improve appearance and confidence” [1]. The Professional Standards for Cosmetic Practice report, published by the Cosmetic Surgical Practice Working Party of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, describes aesthetic practice as “operations and all other invasive medical procedures where the primary aim is the change, restoration, normalization, or improvement of appearance, function, and well-being at the request of an individual” [2]. Although life-threatening incidents are rare in the field of aesthetic practice, complications can lead to drastic changes in a patient’s image, causing extreme distress.

For this reason, only qualified and competent professionals should be allowed to practice. Despite numerous efforts to define cosmetic practices as medical procedures, there have been repeated reports of unlicensed aesthetic practitioners illegally performing medical procedures [3]. A common misconception is that aesthetic procedures are generally harmless. The public therefore tends to overlook the risks and focus instead on the economic benefits of using unlicensed practitioners.

This article reports on an outbreak of devastating facial stigmata caused by a single unlicensed cosmetic practitioner. By addressing current regulations on the practice of medicine and the vulnerability of the public in the healthcare system, this study aims to provide insights on protecting the public from potentially disastrous complications.

During 1 week in November 2021, five patients presented to Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital for the management of facial hypertrophic scars (Fig. 1). Each patient had been treated for skin rejuvenation by the same unlicensed medical practitioner. They reported that the perpetrator was a 72-year-old woman who had run her business for more than 25 years. She frequently changed the contact number and location of her practice. The procedures were scheduled through a personal network and were performed in motels and spas. The procedures involved repetitive dermal needling for bloodletting and evacuation of sebum, and disfigurement occurred within a month. Despite months of needling by the practitioner, aimed at improving the scars, the symptoms were aggravated. The victims presented at our hospital after the practitioner abandoned them, refusing to answer their calls. Although only five patients were treated at our institution, we were informed that dozens of other clients had regular appointments with the same practitioner. The victims were not only stigmatized by the facial disfigurement, but also experienced psychological trauma and severe distress.

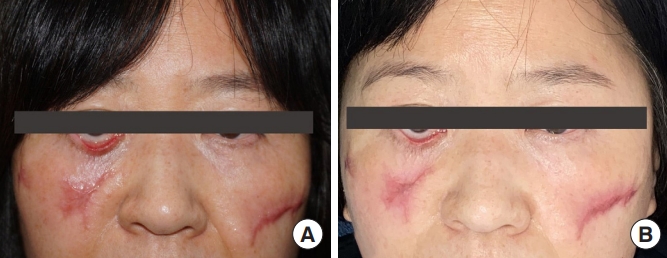

The patients’ characteristics are listed in Table 1. Four female patients and one male patient with a mean age of 57.00±4.56 years were included. The mean duration of treatment was 4.80±0.98 months, and the mean number of procedures was 4.60±1.02. Typically, the patients had multiple erythematous scars on both cheeks (Fig. 1). In one patient, ectropion of the right lower lid was observed due to severe scar contracture (Fig. 2A).

Four patients received serial intralesional triamcinolone injections with silicone sheet application. For the injections, 40 mg/mL of triamcinolone solution was mixed 1:1 with 2% lidocaine solution. A 20 mg/mL solution was injected into the scar until blanching occurred. A total of five injections (once every 4 weeks) were performed. Silicone gel sheeting (Cica-Care; Smith & Nephew, London, UK) was maintained during that period. Resolution of pain and pruritus with improvement of scarring was observed (Fig. 3). The patient with unilateral ectropion caused by scar contracture required subsequent scar release and full-thickness skin grafting (Fig. 2B).

To our knowledge, no previous study has reported the devastating facial stigmata caused by unlicensed and non-medical personnel illegally performing aesthetic procedures. According to a study by Mayer and Goldberg [3], the illegal aesthetic practices involved in lawsuits in the United States in 2013 included buttock injections (n=11), facial injections (n=7), laser facial procedures (n=2), liposuction (n=4), and other types of cosmetic surgery (n=4). Another study by Cho et al. [4] stated that 120 Korean cases were reported in 2008, where permanent makeup tattoos were performed in 22 cases (18.3%), peeling in 19 cases (15.8%), laser therapy in 18 cases (15.0%), and filler injections in 12 cases (10.0%). Other studies focused on atypical microbial infections [5,6] and cutaneous problems caused by laser treatments or filler injections [4,7,8].

According to South Korean law (Article 27 of the Medical Service Act), medical procedures can only be performed by licensed medical personnel. Violators can be punished by imprisonment for up to 5 years or fined according to Article 87 [9,10]. Moreover, non-medical personnel performing medical practices for the purpose of profit can be subject to an additional penalty according to the Act on Special Measures for the Control of Public Health Crimes. Nonetheless, there have been repeated incidents of adverse outcomes caused by procedures performed by unqualified providers.

Medical services delivered by unlicensed providers are a common phenomenon in many low- and middle-income countries [11]. Informal providers are defined as those who sell medical goods and services and dispense health information without the endorsement or permission of state authorities [12]. Informal providers such as traditional birth attendants or medical vendors often provide medical services for those who cannot access public health services. Consequently, it is difficult to detect and intervene in a timely manner when adverse outcomes are caused by unlicensed practitioners. Doctors are distinguished from informal providers by their level of training and knowledge of a delineated set of biomedical concepts and procedures, by their ethical commitment, and by certified guarantees of competence [13].

Although multiple factors contribute to the prevalence of unlicensed aesthetic practices, the primary factor that attracts patients to unlicensed practitioners is cost. In Korea, the National Health Insurance Service provides almost 100% healthcare coverage [14] with a high reimbursement rate. However, the aesthetic practices that are not covered by medical insurance are relatively expensive, and many people are lured to unlicensed practitioners for purely financial reasons.

The second factor is Korea’s dichotomous medical system. Two types of medical doctors (i.e., contemporary medicine doctors and traditional medicine doctors) are educated and licensed to practice in Korea. In addition, the use of acupuncture in Korean medicine is a longstanding tradition that the public respects and uses. It is considered natural and harmless, in contrast to some invasive contemporary medicine practices [15]. Many patients consider minimally invasive plastic surgery procedures such as filler injections or thread lifts to be like acupuncture. Thus, they are less resistant to receiving such procedures, with the expectation that nothing bad will happen. Furthermore, the patients receiving such procedures are often not informed about potential complications.

The final factor is the absence of policies to aid victims and prevent the further spread of unlicensed practices. Although healthcare providers are obligated to report suspected cases of child or elder abuse, the authors contacted the local health authorities but were unable to find a channel to report such an outbreak. We were informed that the only legal way to address the perpetrator’s illegal behavior was for the victims to file a lawsuit. The victims were reluctant to report the matter because they had implicitly agreed to the illegal practices. Since there were no institutional measures to support the victims and suppress further incidents, there was a strong possibility that the number of similar victims would rise.

Numerous unreported cases of illegal aesthetic practices continue to be performed. Because most victims choose illegal procedures for economic reasons, they are less likely to receive qualified treatment for their complications. In the cases presented here, the victims continued receiving illegal procedures from the perpetrator until her desertion. Thus, the scars worsened and management became even more difficult. There is a pressing need to improve the regulatory safety system in this community. The establishment of a financial support system would also allow patients to seek qualified treatment for complications.

In Korea, both the high level of acceptance for complementary medicine and the absence of institutional measures to protect victims and prevent unlicensed aesthetic practitioners from practicing contributed to this outbreak. Although the financial cost of unlicensed aesthetic practices may be low, the price of adverse outcomes can be devastating. Only five patients presented to our institution, but the authors suspect that the number of unreported cases was much greater. As medical experts, plastic surgeons are obligated to educate and inform the public about the harm caused by illegal aesthetic practices. To press for legislation that will prevent further illegal practices, we must report relevant cases to the authorities more often. The authors believe that this study provides insights that can help formulate future policies.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No. HC22RISI0072) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and use of their images.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photographs of facial scars caused by an unlicensed aesthetic practitioner. (A) A 51-year-old woman presented with hypertrophic scars on both malar areas. (B) A 56-year-old woman presented with hypertrophic scars on her left cheek and glabellar area. (C) A 60-year-old woman presented with hypertrophic scars on both malar areas. (D) A 64-year-old man presented with multiple hypertrophic scars on both malar areas and glabellar areas.

Fig. 2.

Ectropion caused by severe scarring. A 54-year-old woman presented with hypertrophic scarring on both malar areas. (A) Scars on her right cheek caused ectropion of the right lower eyelid. (B) Regardless of continued triamcinolone injections and gel sheeting, the ectropion persisted, mandating subsequent surgical correction.

Fig. 3.

Treatment progress. (A) A 60-year-old woman presented with hypertrophic scars causing aggravation of the nasojugal groove. A combination of triamcinolone injections and gel sheeting contributed to progressive improvement in skin texture after 1 month (B), 3 months (C), and 6 months (D).

Table 1.

Characteristics of five patients with facial scars caused by illegal aesthetic treatments

REFERENCES

1. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Cosmetic procedures [Internet]. Arlington Heights, IL: ASPS; c2022 [cited 2022 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/cosmetic-procedures

2. Cosmetic Surgical Practice Working Party. Professional Standards for Cosmetic Practice. London: RCSENG-Professional Standards and Regulation; 2013.

3. Mayer JE, Goldberg DJ. Injuries attributable to cosmetic procedures performed by unlicensed individuals in the United States. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2015;8:35-7.

4. Cho SB, Lee SJ, Shim JH, et al. Case analysis of side effects following illegal therapeutic attempts by non-medical personnel. Korean J Dermatol 2008;46:1507-12.

5. Song JY, Sohn JW, Jeong HW, et al. An outbreak of post-acupuncture cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium abscessus. BMC Infect Dis 2006;6:6.

6. Kim JK, Kim TY, Kim DH, et al. Three cases of primary inoculation tuberculosis as a result of illegal acupuncture. Ann Dermatol 2010;22:341-5.

7. Jang HS, Chung KY, Oh BH. Complications from cosmetic procedures performed by non-professionals: a case analysis and review of treatments. Korean J Dermatol 2014;222-9.

8. Kim DW, Park J, Kim HU, et al. Seventy-four complicated cases referred to a tertiary hospital in Korea after dermatologic procedures. Korean J Dermatol 2015;53:530-7.

9. Medical Service Act, Act No. 27 (Jun 30, 2021).

10. Medical Service Act, Act No. 87 (Jun 30, 2021).

11. Das S, Barnwal P. The need to train uncertified rural practitioners in India. J Int Med Res 2018;46:522-5.

12. Cross J, MacGregor HN. Knowledge, legitimacy and economic practice in informal markets for medicine: a critical review of research. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1593-600.

13. Ahmed SM, Hossain MA. Knowledge and practice of unqualified and semi-qualified allopathic providers in rural Bangladesh: implications for the HRH problem. Health Policy 2007;84:332-43.

14. OECE iLibrary. Population coverage for a core set of services [Internet]. Paris: OECD; c2019 [cited 2022 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ab673b0d-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/ab673b0d-en#figure-d1e4373