|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 28(4); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Known to be chemically inert, Aquafilling filler has been widely used in local aesthetic clinics in South Korea for breast augmentation. However, Aquafilling is only approved as a dermal filler and is not approved as an injectable filler for breast augmentation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Several reports of complications following large-volume Aquafilling injections in the breast have been published. In this study, an HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)-infected transgender patient presented to the emergency room with a purulent infection of the breast and systemic fever. The patient had a history of large-volume Aquafilling injection in both breasts 3 years earlier to obtain a feminized appearance of the breasts. After using intravenous antibiotics and performing several surgical debridements over 4 weeks, the overall inflammatory response subsided. The skin defect site was covered successfully using an Integra Wound Matrix Dressing and there were no recurrent complications over 2 years of follow-up visits. Before injecting Aquafilling to augment patients’ breasts, a thorough consultation is mandatory, and doctors must notify patients that the risk of complications may be relatively high. Furthermore, any fillers including Aquafilling must not be used for unapproved purposes.

Aquafilling gel (Biomedica, Prague, Czech Republic) is a non-degradable injectable dermal filler approved by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2013. Despite its approval as a dermal filler, it has not been approved as a breast augmentation filler. However, it has been used recently as an alternative option for breast augmentation, usually by general physicians in local aesthetic clinics who are not board-certified in plastic surgery or dermatology in South Korea [1]. It is made of 2% polyacrylamide-co-N,N’-methylene-bis-acrylamide and 98% sodium chloride solution (0.9%) [1]. Known to be chemically inert, the use of Aquafilling filler for breast augmentation has increased in the local aesthetic clinics of South Korea in the last few years [1]. However, complications following Aquafilling injection in the breast, such as pain, infection, migration, and even sepsis, have been reported [2]. There are few studies dealing with the complications of using large-volume Aquafilling injections in the breast [1]. We found no reported cases dealing with the complication of a large skin defect of the breast due to a severely purulent infection. Therefore, we report a case of severe complication following large-volume Aquafilling injection in both breasts of a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected transgender patient.

A 33-year-old male-to-female transgender patient had a history of 275 cc of Aquafilling injected into each breast 3 years ago in a local aesthetic clinic. The patient started to feel mild mastalgia and a sensation of heat in the breast 6 months ago and visited the local clinic where she had undergone the filler injection. The patient’s condition was misdiagnosed as a temporary symptom, and no adequate treatment was provided before skin necrosis, purulent infection of the breast, and systemic fever developed. The patient presented to the emergency room complaining of severe pain, pus-like discharge, skin necrosis, and a sensation of heat in the breast. Initially, her body temperature was 37.5°C and her blood pressure was in a normal range. Overall, an erythematous skin change of both breasts was observed and a large amount of viscous pus-like yellow discharge was oozing from three holes in the upper pole of the left breast (Fig. 1A). After removing a massive amount of purulent discharge, a 5×5 cm skin defect was left (Fig. 1B). As the skin flap between the two breasts was thinned and detached from the sternum, symmastia was observed. The viability of the skin flap around the skin defect was very poor.

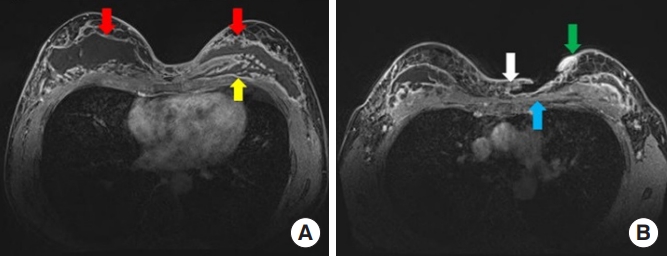

The patient was known to be HIV-infected and was taking HIV medications daily. In a serologic test, the HIV RNA viral load was below 20 copies/mL, T cells were within the normal range, the CD4/CD8 ratio was normal, and the absolute CD4 count was normal. The patient had normal immune function despite her HIV infection. The white blood cell count was slightly elevated at 11.25×109/L and the C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 24.40 mg/dL. A bacterial culture of the discharge showed methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus growth, and appropriate intravenous antibiotics were used for treatment. Preoperative contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging showed retroglandular fluid collection and infiltration into the pectoralis muscle in both breasts (Fig. 2A), symmastia and subcutaneous inflammation in the upper pole of the left breast (Fig. 2B).

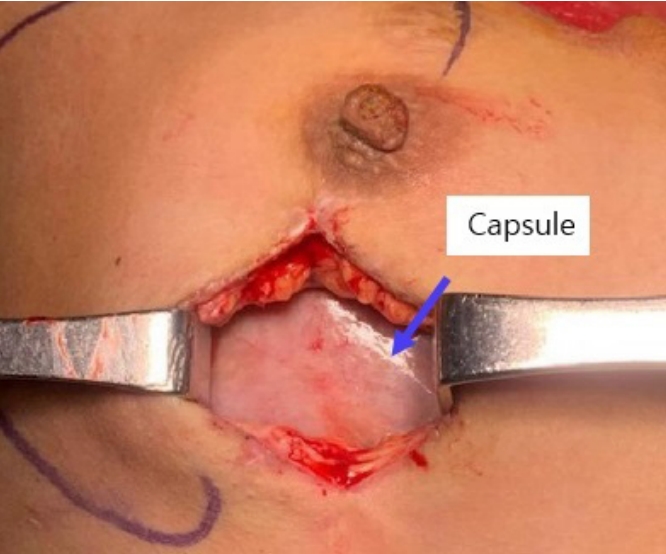

After 2 days of daily dressing including drainage of the resident filler and copious irrigation via the skin defect site, the patient’s body temperature recovered to the normal range and the CRP decreased to 4.47 mg/dL. On admission day 3, the first operation including surgical drainage of the residual filler and bloody pus was done. Under general anesthesia, curettage and debridement of the visibly infiltrated filler nodule in the subcutaneous layer and pectoralis muscle layer, as well as contaminated tissue was done through a horizontal lateral radial incision. The wound was semi-closed to allow drainage of remnant filler and pus. Two weeks after the first operation, capsulectomy was performed (Fig. 3). Within 4 weeks, four operations including surgical drainage, tissue debridement, capsulectomy, and copious irrigation were performed under general anesthesia, and then both lateral radial incision sites were completely closed. The detached skin flap around the skin defect healed and the patient’s CRP decreased to 0.73 mg/dL. However, a substantial step deformity of the skin defect and the surrounding skin remained.

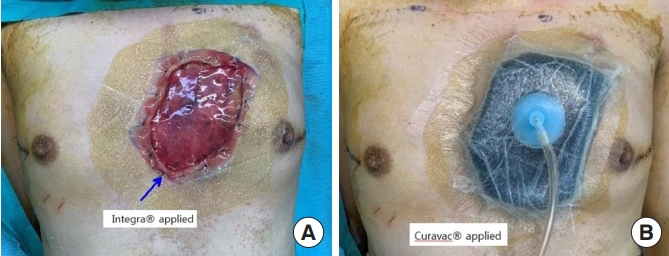

Integra Matrix Wound Dressing (Integra LifeSciences, Princeton, NJ, USA) was applied to the fresh granulation tissue of the skin defect site to reduce the step deformity (Fig. 4A). Numerous holes were made on the Integra Wound Matrix Dressing by stab incision for drainage of exudate. A negative-pressure wound therapy device (Curavac; CGBio, Seoul, Korea) was applied and maintained for 3 weeks (Fig. 4B). After 3 weeks, the uppermost silicone layer of the Integra Wound Matrix Dressing was removed and a split-thickness skin graft was applied to the regenerated subcutaneous layer of the skin defect site. The patient was discharged 8 weeks after admission. A small amount of residual filler infiltrating the subcutaneous layer exuded from around the skin defect site but was cleared with minimal curettage and healed by secondary intention. After 2 years of outpatient clinic follow-up visits, no evidence of recurrent infection, mastalgia, heat sensation, fever, or CRP elevation was observed. The skin defect site was reconstructed without a significant step deformity compared to the normal surrounding skin (Fig. 5).

Augmentation mammoplasty is one of the most common plastic surgery procedures performed for aesthetic reasons [3]. Although silicone implants are the primary means of achieving breast volume augmentation [3], surgical incision and dissection under sedation or general anesthesia to make pockets for placing these implants (i.e., subglandular, submuscular, partial muscular, subfascial pockets) are necessary [4]. Thus, the process of implant augmentation mammoplasty can be perceived as an invasive procedure by prospective patients. In addition, an unnatural appearance and texture, malposition, asymmetry, nipple numbness, scarring, contracture, hematoma, seroma, infection, and the possibility of implant rupture are risks of implant augmentation mammoplasty [5]. For these reasons, injecting autologous fat or filler substances into the breast emerged as a simple alternative technique for breast augmentation.

However, autologous fat grafting in the breast also has problems such as resorption, necrosis, and calcification. Resorption of fat makes it hard to predict the final outcome of the augmentation in terms of volume. Necrosis and calcification in the breast may potentially interfere with breast cancer screening [6]. Additionally, thin women with insufficient fat deposits on their abdomen or thigh are not suitable candidates for autologous fat grafting of the breasts [7].

Among the various injectable filler substances such as paraffin, liquid silicone, and polyacrylamide gel (PAAG), Aquafilling gel, made of 2% polyacrylamide-co-N,N’-methylene-bis-acrylamide and 98% sodium chloride solution (0.9%), has been widely used for breast augmentation in South Korea because of its chemical inertness [1]. The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety approved the use of Aquafilling gel as a dermal filler for the temporary improvement of facial wrinkles, facial asymmetry, and to shape and augment lip volume in 2013. Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration did not approve the usage of Aquafilling for breast augmentation [8], it has been used as a breast augmentation filler by general physicians who are not board-certified in plastic surgery or dermatology in local aesthetic clinics in South Korea [1]. Consequently, complications following Aquafilling injections in the breast such as pain, infection, migration, and sepsis have been reported [1-3,8].

Shin et al. [9] reported the temporary usage of Aquafilling for correcting shape and size after breast augmentation with silicone implants. However, they injected relatively small volumes of Aquafilling between the silicone implant and the skin of the breast. Namgoong et al. [1] recently reported on the clinical experience of patients who had large volumes of Aquafilling injected into their breasts. When used in large volumes, Aquafilling is usually injected into deep layers such as the subglandular layer, making it hard to detect the early signs of infection, unlike similar injections in subcutaneous layers [1].

In this study, early diagnosis and timely treatment of the patient failed. As a result, the patient has an irreversible, large scar on her breast despite our best efforts. Every change in sensation in the breasts of patients after augmentation should be investigated, even when they are ambiguous or seem trivial. We recommend anticipatory imaging, such as ultrasonography or chest computed tomography, as well as serological tests including inflammatory markers for early diagnosis and to minimize damage to the breast due to inflammatory changes.

The patient in this study was HIV-infected, and we initially assumed that the purulent infection could be associated with her immunocompromised condition. However, after checking her HIV RNA viral load, T cell count, CD4/CD8 ratio, and absolute CD4 count, we found that the patient’s immune system was normal. She was also taking daily HIV medications. According to Jung et al. [3], Aquafilling is a hydrophilic liquid that absorbs body fluids and exudates, so that a large volume of injected Aquafilling gel itself can be a nutrient-rich medium for bacterial growth, even in patients with normal immunity. The delayed infection after an Aquafilling injection 3 years previously can be categorized as a late inflammatory reaction [10]. The etiopathogenesis of late inflammatory reactions remains unclear, but several hypotheses have been suggested, such as bacterial contamination, foreign body reaction, delayed-type hypersensitivity (type IV) reaction, and reactions to adjuvant-based filler, as in vaccinations [10].

Jin et al. [11] classified the complications of PAAG fillers in breast augmentation by their anatomical distribution and suggested a diagnosis and treatment algorithm for each case. Namgoong et al. [1] also suggested a treatment protocol based on tissue culture results and serological test results. Having researched the literature on breast filler-associated complications, we performed multiple surgical debridements including capsulectomy, used an open-wound dressing with intravenous antibiotics over a long period of time, and we delayed reconstruction of the breast until disappearance of the inflammatory reaction was assured. Nevertheless, there was recurrence of a minor complication in the form of exudative remnant subcutaneous filler around the skin defect site. In this case, curettage and secondary intention healing were enough to treat the recurrence.

In our study, delayed reconstruction of the skin defect was done using Integra Wound Matrix Dressing. A dermal regeneration template, the Integra Wound Matrix Dressing is a ready-to-use porous matrix of cross-linked bovine tendon collagen and glycosaminoglycan [12]. After application of Integra Wound Matrix Dressing to the skin defect, the native fibroblasts, macrophages, and lymphocytes, as well as new capillaries, infiltrate the matrix [13]. Within 3 weeks, the inner layer becomes degraded and is replaced with an endogenous collagen matrix, and finally a neodermis is formed [13,14]. In this study, a split-thickness skin graft was done over the neodermis after removing the outermost silicone layer. The neodermis formed from the Integra Wound Matrix Dressing provided additional thickness to the dermal portion, so that the step deformity of the skin defect could be minimized [14]. This method would be a useful modality for reconstruction of skin defects with accompanying step deformities.

The complication rate following injection of a PAAG filler was shown to be 18.3% in a Chinese study [15]. There are slight molecular differences between the PAAG filler and Aquafilling, but the overall composition of both fillers is quite similar [1]. Although there are no conclusive statistical studies dealing with the complication rate following injection Aquafilling, the safety of using Aquafilling in large volumes for breast augmentation seems to be inconclusive. A thorough consultation with patients is essential before injecting Aquafilling for breast augmentation. Doctors must notify patients that the risk of complications may be relatively high. Furthermore, doctors must not use filler products, including Aquafilling, for unapproved purposes.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Busan Paik Hospital (IRB No. 2021-12-035).

Patient consent

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of her images.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative photographs. (A) Overall erythematous skin color change and pus-like discharge from three holes in the upper pole of the left breast. (B) A 5×5 cm skin defect was left in the left upper pole of the breast after urgent debridement and irrigation at the emergency room.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative image study. (A) Contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging showed retroglandular fluid collection (red arrows) and infiltration into the pectoralis muscle (yellow arrow) in both breasts. (B) Contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging showed skin and parenchymal tissue defect (blue arrow), symmastia (white arrow), and inflammatory changes of the subcutaneous tissue around the skin defect (green arrow) in the upper pole of the left breast.

Fig. 3.

Capsule formation around the filler injected pocket was observed after complete removal of the injected filler and capsulectomy was performed in the second operation.

Fig. 4.

Procedures for reducing the step deformity. (A) Integra Wound Matrix Dressing was applied to the fresh granulation tissue of the skin defect site to reduce the step deformity. (B) A negative-pressure wound therapy device (Curavac) was applied after making numerous holes in the Integra Wound Matrix Dressing by stab incision for drainage of exudate and then maintained for 3 weeks.

REFERENCES

1. Namgoong S, Kim HK, Hwang Y, et al. Clinical experience with treatment of Aquafilling filler-associated complications: a retrospective study of 146 cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2020;44:1997-2007.

2. Chalcarz M, Zurawski J. Injection of Aquafilling® for breast augmentation causes inflammatory responses independent of visible symptoms. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2021;45:481-90.

3. Jung BK, Yun IS, Kim YS, et al. Complication of Aquafilling® Gel injection for breast augmentation: case report of one case and review of literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2018;42:1252-6.

4. Vogt PM, Mackowski MS, Dastagir K. Implant-based multiplane breast augmentation—a personal surgical concept for dynamic implant–tissue interaction providing sustainable shape stability. Eur J Plast Surg 2021;44:609-23.

5. Shen Z, Chen X, Sun J, et al. A comparative assessment of three planes of implant placement in breast augmentation: a Bayesian analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2019;72:1986-95.

6. Lin JY, Song P, Pu LL. Management of fat necrosis after autologous fat transplantation for breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2018;142:665e-673e.

7. Li FC, Chen B, Cheng L. Breast augmentation with autologous fat injection: a report of 105 cases. Ann Plast Surg 2014;73(Suppl 1):S37-42.

8. Roh TS. Letter: Position Statement of Korean Academic Society of Aesthetic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery: concerning the use of Aquafilling® for breast augmentation. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2016;22:45-6.

9. Shin JH, Suh JS, Yang SG. Correcting shape and size using temporary filler after breast augmentation with silicone implants. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2015;21:124-6.

10. Bachour Y, Bekkenk MW, Rustemeyer T, et al. Late inflammatory reactions in patients with soft tissue fillers after SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination: a systematic review of the literature. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022;21:1361-8.

11. Jin R, Luo X, Wang X, et al. Complications and treatment strategy after breast augmentation by polyacrylamide hydrogel injection: summary of 10-year clinical experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2018;42:402-9.

12. Spater T, Frueh FS, Metzger W, et al. In vivo biocompatibility, vascularization, and incorporation of Integra® dermal regenerative template and flowable wound matrix. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2018;106:52-60.

13. Rashid OM, Nagahashi M, Takabe K. Management of massive soft tissue defects: the use of INTEGRA® artificial skin after necrotizing soft tissue infection of the chest. J Thorac Dis 2012;4:331-5.