|

|

- Search

| Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg > Volume 29(4); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Surgical scars subjected to excessive tension tend to widen and become hypertrophic due to strong mechanical stretching forces. In this study, we evaluated the clinical outcomes of combined intraoperative and postoperative long-term tension reduction techniques for the revision of scars subjected to excessive tension.

Methods

In total, 64 cases (62 patients) underwent scar revision and were followed for 6 months or more. The long-term tension reduction technique included intraoperative subcutaneous fascial and deep dermal closure using nonabsorbable nylon sutures and postoperative long-term skin taping for 3 to 8 months. The final scars were objectively evaluated using our Linear Scar Evaluation Scale (LiSES, 0-10 scale), which consisted of five categories: width, height, color, texture, and overall appearance.

Results

All 64 cases healed successfully, without early postoperative complications such as infection or dehiscence. The follow-up period ranged from 6 months to 6 years. The LiSES scores ranged from 5 to 10 (mean: 8.2). Fifty-one cases (79.6%) received a score of 8 to 10, which was assessed as ŌĆ£very goodŌĆØ by the evaluator. Two cases with a score of 5 (3%) showed partial hypertrophic scars at the last follow-up visit. All patients were highly satisfied with their final outcomes, including the two patients who experienced partial hypertrophic scars.

Surgical scars that are subjected to significant tension tend to widen and become hypertrophic. Levenson et al. [1] reported on the healing process of rat skin wounds, wherein the maximum breaking strength of the wounded skin recovered to approximately 80% of normal unwounded skin 3 months after injury. Melis et al. [2] described the long-term outcomes of wounds closed under significant tension, wherein the size of residual scars after 7 years remained > 50% of the original lesion size. Moreover, 83% of the total scar formation occurred within 6 months postoperatively, while 57% occurred within 3 months postoperatively. This scarring may be caused by excessive mechanical stretching of the dermal wound, which intensively modulates cellular behavior with consequential chronic inflammation during the proliferative and remodeling phases of the wound-healing process. This results in hypertrophic and widened scar formation [3]; therefore, long-term reduction of skin tension at the wound edges should be continued until the dermal wound achieves maximum tensile strength and is stabilized, at least 3 to 6 months postoperatively.

Several techniques for long-term tension reduction have been established, including intraoperative fascial [4,5] and dermal closure using durable suture materials [6-8] and postoperative long-term paper taping on the skin surface [9-11]. These techniques provide long-term dermal support to reduce the stretching force on the dermis of the wound edges until the scar is stabilized and matured. Therefore, a combination of intraoperative and postoperative techniques may help achieve satisfactory aesthetic outcomes with inconspicuous scars. However, this combined technique has not yet been presented in the literature.

In the current study, we combined intraoperative suturing of the subcutaneous fascia (i.e., superficial fascia) and the deep dermis using nylon sutures with postoperative long-term skin taping for scar revision in areas subjected to excessive tension. The patients were followed and we evaluated their clinical outcomes.

Between 2010 and 2022, 86 patients underwent scar revision in areas subjected to excessive tension for one or more of the following reasons: (1) the anatomical region, such as the chest, shoulder, or joints, created excessive skin tension; (2) the longitudinal axis of the scar was perpendicular to the relaxed skin tension line (RSTL) or wrinkle lines; and (3) the presence of skin deficits following previous scar excision or contracture. Sixty-two patients (64 cases) who were followed up for Ōēź 6 months postoperatively were included in this study. The patients were aged 2 to 76 years. Preoperatively, 33 cases had wide or depressed scars, 26 cases had hypertrophic scars, and five cases had keloid scars. The scars were located on the face (n = 33), lower neck (n = 4), chest (n = 4), shoulder (n = 3), clavicle (n = 1), abdomen (n = 2), forearm (n = 4), arm (n = 3), elbow (n = 5), wrist (n = 2), knee (n = 2), and ankle (n = 1). In all cases, the scar tissues involved subcutaneous fascia or deeper layers.

Our combined method for long-term tension reduction in dermal wounds included intraoperative subcutaneous fascial and deep dermal closure using nonabsorbable nylon sutures plus postoperative long-term skin taping.

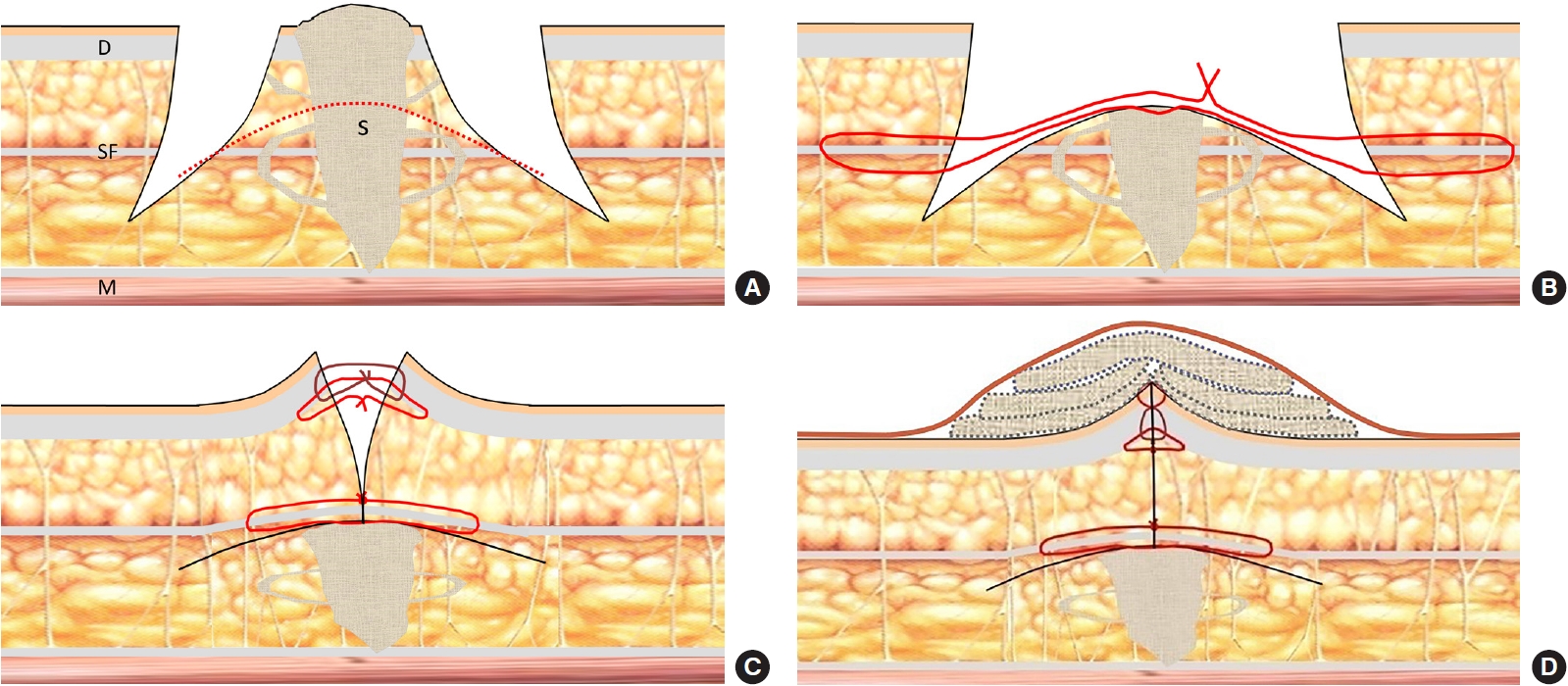

When the scar axis followed the RSTL, or when the scar shape was round or oval, scar excisions were designed in a fusiform shape. When the scar axis was vertical or oblique to the RSTL, the excisions were designed in a zigzag shape, as in W- or Z-plasty. After local anesthetic infiltration, a beveled incision of the skin and subcutaneous tissue layer was created along the designed line of the subcutaneous fascia on the trunk and extremities, and the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (superficial muscle fascia of the frontalis or platysma muscle) on the face and neck. Subsequently, limited undermining was performed under the subcutaneous fascia or superficial musculoaponeurotic system for a full release of scar adhesion (Fig. 1A).

The superficial layers of the subcutaneous and scar tissues were tangentially excised, while the deep layer was preserved to avoid dead space and allow easier skin eversion after wound closure, as well as to prevent postoperative scar depression. Subsequently, long-term tension reduction suturing of the subcutaneous fascia was performed using 6-0 or 5-0 nylon sutures (Ethilon; Ethicon) on the face and 4-0 or 5-0 nylon sutures on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 1B). The planned bite distance of the subcutaneous fascial suture was as far as possible from the wound surface (1.5ŌĆō2 cm on the face; 2ŌĆō3 cm on the trunk and extremities). The interstitch distance of the fascial suture was 1 to 2 cm. To avoid the loosening of sutures or subcutaneous tissue damage, subcutaneous fat tissue was not included during fascial closure.

Next, long-term tension reduction suturing of the deep dermis was performed using 7-0 or 6-0 nylon sutures (Fig. 1C). The interstitch distance of the deep dermal sutures was 1 to 1.5 cm. Additional dermal closure with a short bite distance between the deep dermal sutures was performed using 6-0 or 5-0 polyglactin 910 sutures (Vicryl; Ethicon) to obtain sufficient dermal contact and skin eversion in a mountain-range shape. The skin edges of the wounds were then approximated in a tension-free state. Finally, the superficial skin was closed using 7-0 or 6-0 nylon sutures with short suture bite distances to achieve an accurate approximation (Fig. 1D).

For wound coverage, long strips of saline-moistened gauze were placed along both sides of the suture line after topically applying an antibiotic ointment, and the wound was mildly compressed with paper tapes (Fig. 1D). This dressing technique was performed to maintain skin eversion in a mountain-range shape until both surfaces of the dermal wound were sufficiently attached together (approximately 7ŌĆō10 days postoperatively). The superficial skin stitches were removed after 5 days on the face and 7 to 8 days on the trunk and extremities.

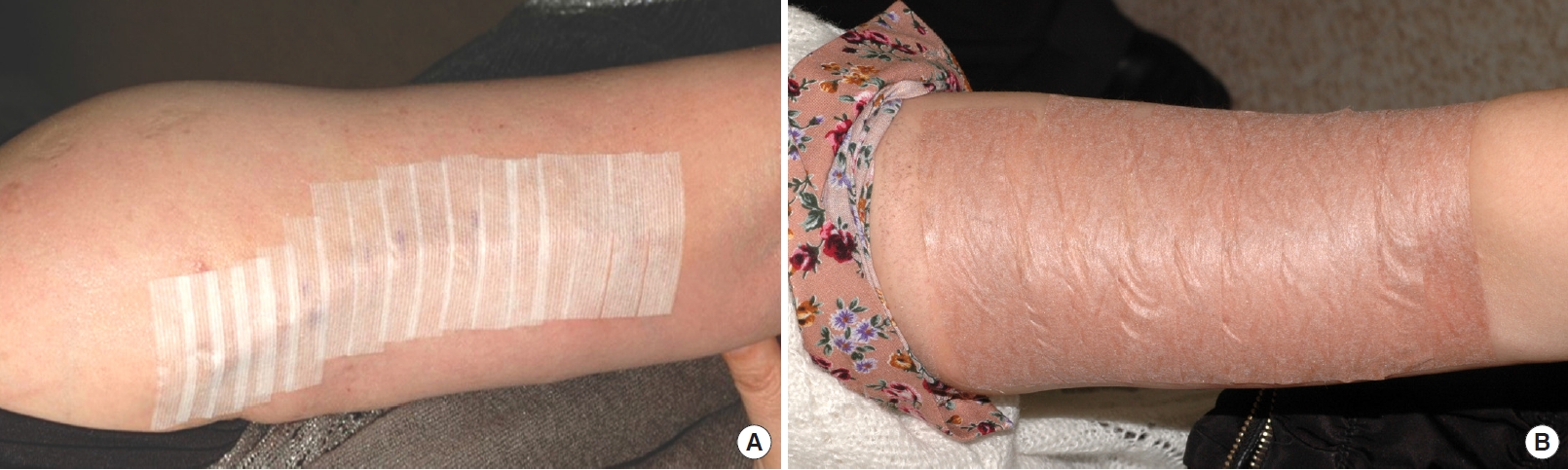

Long-term postoperative paper taping of the skin was initiated after removing the skin stitches and mild compressive dressing. Multiple strips of adhesive paper skin tape (Steri-Strip or Micropore; 3M) were applied perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the suture line, and the skin on both sides of the suture line was gently pulled towards the suture line to maintain skin eversion (Fig. 2). To decrease the risk of blister formation from excessive skin pulling, the skin tapes were applied while the surrounding skin was maximally relaxed by gentle, manual skin pulling and/or position changes, including joint extension, anterior folding of the chest, or facial rotation toward the application site. The skin tapes overlapped, and the length of the tapes was Ōēź 3 cm on the face and Ōēź 10 cm on the trunk and extremities. They were removed and changed every 1 to 2 days. After tape removal, the entire operative region, including the surrounding skin, was washed with water and soap, moisturized by topically applying moisturizing lotion or hyaluronic acid gel, and then exposed to air for 4 hours. Prior to retaping, a protective or barrier film spray was applied to the skin surface to reduce adverse reactions. Skin taping was maintained for at least 3 months for the face and 6 months for the trunk and extremities, until the scar was stabilized.

During the follow-up period, we checked for adverse reactions, such as dermatitis or blister formation; if these occurred, skin taping was temporarily paused, and intensive care using steroid creams and antibiotic ointments with or without a hydrocolloid dressing was administered until subsidence. Patients were required to revisit every month for the first 6 months, and then every 2 to 3 months thereafter until the scar redness was barely noticeable.

To objectively evaluate clinical outcomes, photographs and medical records of the final scar at the last follow-up visit were evaluated by an independent physician using our Linear Scar Evaluation Scale (LiSES). The scale consisted of five categories: width, height, color, texture, and overall appearance (Table 1). To establish the LiSES, we modified the Stony Brook (or Hollander) Scar Evaluation Scale to meet our evaluation criteria for the long-term appearance of lacerations or incisional scars [12]. The five categories of the LiSES were each assigned a score from 0 to 2, and the total sum was scored from 0 to 10.

The surgical wounds in all 64 cases healed successfully without early postoperative complications such as infection, impaired skin circulation, delayed wound healing, or wound dehiscence. The follow-up period ranged from 6 months to 6 years (mean: 16.5 months). During the follow-up period, nine patients (13.6%) exhibited adverse reactions to taping (6 itchy skin rashes or 3 blisters) that were treated by topically applying hydrocortisone and antibiotic ointments, with or without a hydrocolloid dressing. No late complications associated with the fascial and dermal nylon sutures, such as subcutaneous nodules, stitch exposure, or stitch abscess, were detected. The skin taping period was 3 months on the face and 6 mon┬Łths on the trunk and extremities, excluding three cases where skin taping occurred for 4 months on the face and 8 months on the elbow.

All postoperative scars appeared fine and linear for at least 2 months after surgery. When skin eversion with postoperative taping was maintained for Ōēź 3 months on the face or Ōēź 6 months on the trunk or extremities, the final scar was nearly inconspicuous (Fig. 3). In some cases, everted skin along the suture line was flattened within 2 months despite continuous skin taping, followed by scar depression or widening. Partial hypertrophic scars occurred in five cases with wide hypertrophic or keloid scars. In three cases, these completely resolved after intermittent triamcinolone injections; however, partial slightly hypertrophic scars remained in two cases (3.1%) until the final follow-up (Fig. 4).

The LiSES scores ranged from 5 to 10 (mean: 8.2; 5 [n = 2], 6 [n = 2], 7 [n = 9], 8 [n = 25], 9 [n = 17], and 10 [n = 9]). Fifty-one cases (79.6%) received a score of 8 to 10 on the LiSES, which was assessed as ŌĆ£very goodŌĆØ by the evaluating physician (Fig. 3). Two cases with a score of 5 exhibited partial hypertrophic scars at the last follow-up visit (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, all patients were significantly satisfied with their final outcomes, even those with partial hypertrophic scars.

Scar revision, especially of wide scars in areas subjected to excessive tension, is challenging for plastic surgeons. There is a high risk of abnormal scar formation, including scar widening, depression, or hypertrophy caused by the strong mechanical stretching force on the dermal wound. Occasionally, the final scar may be worse than the preoperative scar. Therefore, long-term tension reduction in dermal wounds is crucial to obtain aesthetically satisfactory outcomes in the presence of excessive skin tension.

Long-term tension reduction techniques include intraoperative fascial and/or dermal closure using durable suture materials [4-8] and postoperative long-term paper taping [9-11]. Ogawa et al. [4] emphasized the importance of muscular and subcutaneous fascial closure for reducing tension on the wound edge. However, skeletal muscle fascia closure is particularly challenging, even impossible, on the face or sites without underlying muscles, such as the scalp. Many surgeons have reported that dermal closure using durable suture materials can effectively reduce dermal tension and decrease scar stretching [6-8]. Therefore, we used a combination of deep dermal and subcutaneous fascial closure using durable suture materials for intraoperative tension reduction to effectively prevent abnormal scarring.

Absorbable polydioxanone (PDO) sutures, commonly used in fascial and dermal closure, are useful for tissue approximation under tension for up to 6 weeks [4,6,7,13]; however, Levenson et al. [1] showed that the maximum breaking strength of an incision scar in rats was achieved approximately 3 months after injury. Theoretically, an ideal suture material should retain sufficient tensile strength for at least 3 months. Therefore, we doubt that PDO sutures would be useful for fascial and dermal closure in wounds with excessive tension. Furthermore, PDO sutures require at least four throws to secure a knot, and because of the larger knots, palpable subcutaneous nodules and suture granulomas are prone to occur [4,14,15]. Therefore, we prefer nonabsorbable nylon sutures, particularly for deep dermal suturing, because they require fewer throws to a secure knot and result in smaller knots [14,16]. Furthermore, there are no reports of significant inflammatory response or foreign body reaction to nylon sutures within the tissue. To prevent complications such as knot exposure, the knot end of the suture should be cut short, and the knot should be buried underneath the deep dermis. In our study, no complications related to the nylon sutures or knots were observed.

We had previously found that intraoperative tension reduction sutures allowed for sufficient skin eversion and tension-free closure. However, when postoperative dermal support was not provided, the initially everted skin gradually depressed and flattened within the first few weeks or months, frequently resulting in scar depression, spreading, or hypertrophy. We believe that this may have been due to the gradual splitting of collagen bundles in the subcutaneous fascia or dermis caused by the tying force of the sutures and consequent loss of retention force. Therefore, long-term postoperative dermal support appears to be necessary to achieve optimal outcomes in scar revision for areas subjected to excessive tension.

Postoperative paper taping was introduced as an effective technique to reduce or prevent scar widening or hypertrophy [9-11]. In most clinical studies, paper tape was applied to surgical wounds for 12 weeks; however, the maximum breaking strength of a wound scar was shown to occur at 3 months in the incisional wounds of rat skin [1]. In the incisional wounds of human skin subjected to stronger tension, hypertrophic or stretched scars cannot be completely prevented by taping for 12 weeks [10]. Furthermore, in excisional wounds closed under excessive tension, the scar may gradually increase and not mature for a prolonged period, resulting in a stretched, hypertrophic scar [2]. Therefore, we suggest that skin taping be maintained for 3 to 6 months after scar revision in areas subjected to excessive tension. In addition, in cases where prominent muscle activity is expected, such as a horizontal scar at the glabella or a vertical scar at the forehead, botulinum toxin injections at the corrugator or frontalis muscles would help prevent scar widening.

Patients may find it challenging, especially during the summer, to maintain long-term skin taping if dermatitis or blister formation occurs. Therefore, the importance of skin care is emphasized to all patients. When adverse reactions occur, taping is temporarily paused and the intensive application of topical steroid creams or antibiotic ointments is performed. To prevent the complete cessation of taping, a thin sheet of hydrocolloid dressing can be applied to the skin on either side of the linear scar, thus allowing taping to the dressing instead of to skin.

In our study, a combination of intraoperative and postoperative tension reduction techniques resulted in better than anticipated aesthetic outcomes. Fifty-five cases (79.6%) with a LiSES score of 8 to 10 were evaluated as ŌĆ£very goodŌĆØ (Fig. 3), and all patients were highly satisfied with their final outcomes, even the two cases with partial hypertrophic scars and LiSES scores of 5 (Fig. 4). Therefore, we believe that a combination of intraoperative and postoperative long-term tension reduction techniques can help achieve long-term dermal support and satisfactory aesthetic outcomes for scar revision in areas subjected to excessive tension.

Notes

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University Hospital (IRB No. 2023-03-022) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and use of their images.

Fig.┬Ā1.

Intraoperative long-term tension reduction technique during scar revision, with subcutaneous fascial and deep dermal closure using nonabsorbable nylon sutures (red). (A) A beveled skin-fat incision and tangential excision (dotted line) of the superficial layer including the scar tissue. (B) Subcutaneous fascial closure using nylon sutures (interstitch distance: 1ŌĆō2 cm). (C) Deep dermal closure using nylon sutures (interstitch distance: 1ŌĆō1.5 cm) and additional dermal closure using polyglactin 910 (dark brown). (D) Superficial skin closure using nylon sutures and wound coverage using saline-moistened gauze strips to maintain skin eversion. S, scar; D, dermis; SF, subcutaneous fascia; M, muscle.

Fig.┬Ā2.

(A, B) Postoperative paper taping for long-term tension reduction after scar revision surgery. Long strips of paper tape (Ōēź3 cm on the face and Ōēź10 cm on the trunk and extremities) to maintain skin eversion and prevent scar stretching or hypertrophy.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Cases of scar revision in areas subjected to excessive tension with preoperative (left) and postoperative (right) photographs. (A) A wide hypertrophic surgical scar along the right mandibular margin of a 45-year-old man who underwent two previous scar revisions of a burn scar. (B) Postoperative photograph at 73 months with a Linear Scar Evaluation Scale (LiSES) score of 8. Taping was maintained for 6 months postoperatively. (C) A depressed laceration scar on the right malar area of a 51-year-old man. (D) Postoperative photograph at 35 months with a LiSES score of 10. Taping was maintained for 4 months postoperatively. (E) A wide, depressed laceration scar on the glabella and left sub-brow area of a 43-year-old woman. (F) Postoperative photograph at 6 months with a LiSES score of 9. Taping was maintained for 4 months postoperatively. (G) A hypertrophic sternotomy scar on the chest of a 31-year-old man. (H) Postoperative photograph at 61 months with a LiSES score of 8. Taping was maintained for 6 months postoperatively. (I) A hypertrophic burn scar on the right clavicle of a 2-year-old boy. (J) Postoperative photograph at 6 months with a LiSES score of 10. Taping was maintained for 6 months postoperatively.

Fig.┬Ā4.

A case of partial hypertrophic scar formation after scar revision. (A) A long hypertrophic incisional scar on the left arm of a 28-year-old woman. (B) Postoperative photograph at 17 months with a Linear Scar Evaluation Scale score of 5.

Table┬Ā1.

Linear Scar Evaluation Scale

| Evaluation category | Point |

|---|---|

| Width | |

| ŌĆā> 2 mm | 0 |

| ŌĆāŌēż 2 mm | 1 |

| ŌĆāŌēż 1 mm | 2 |

| Height | |

| ŌĆāObviously depressed or elevated | 0 |

| ŌĆāSlightly depressed or elevated | 1 |

| ŌĆāFlat | 2 |

| Color | |

| ŌĆāObviously darker than the surrounding skin (red, purple, or black) | 0 |

| ŌĆāSlightly darker | 1 |

| ŌĆāAlmost indistinguishable or lighter | 2 |

| Texture | |

| ŌĆāObviously different form the surrounding skin (suture marks, shine, wrinkle, or edge sharpness) | 0 |

| ŌĆāSlightly different | 1 |

| ŌĆāAlmost indistinguishable | 2 |

| Overall appearance | |

| ŌĆāPoor | 0 |

| ŌĆāFair | 1 |

| ŌĆāGood | 2 |

| Total scorea) | 10 |

REFERENCES

1. Levenson SM, Geever EF, Crowley LV, et al. The healing of rat skin wounds. Ann Surg 1965;161:293-308.

2. Melis P, van Noorden CJ, van der Horst CM. Long-term results of wounds closed under a significant amount of tension. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:259-65.

3. Darby IA, Desmouliere A. Scar formation: cellular mechanisms. In: Teot L, Mustoe TA, Middelkoop E, et al., editors. Textbook on scar management: state of the art management and emerging technologies. Springer; 2020. p. 19-26.

4. Ogawa R, Akaishi S, Huang C, et al. Clinical applications of basic research that shows reducing skin tension could prevent and treat abnormal scarring: the importance of fascial/subcutaneous tensile reduction sutures and flap surgery for keloid and hypertrophic scar reconstruction. J Nippon Med Sch 2011;78:68-76.

5. Nordstrom RE, Nordstrom RM. Absorbable versus nonabsorbable sutures to prevent postoperative stretching of wound area. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986;78:186-90.

6. Guyuron B, Vaughan C. Comparison of polydioxanone and polyglactin 910 in intradermal repair. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;98:817-20.

7. Gupta D, Sharma U, Chauhan S, et al. Improved outcomes of scar revision with the use of polydioxanone suture in comparison to polyglactin 910: a randomized controlled trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2018;71:1159-63.

8. Elliot D, Mahaffey PJ. The stretched scar: the benefit of prolonged dermal support. Br J Plast Surg 1989;42:74-8.

9. Reiffel RS. Prevention of hypertrophic scars by long-term paper tape application. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;96:1715-8.

10. Atkinson JA, McKenna KT, Barnett AG, et al. A randomized, controlled trial to determine the efficacy of paper tape in preventing hypertrophic scar formation in surgical incisions that traverse LangerŌĆÖs skin tension lines. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;116:1648-56.

11. Lin YS, Ting PS, Hsu KC. Comparison of silicone sheets and paper tape for the management of postoperative scars: a randomized comparative study. Adv Skin Wound Care 2020;33:1-6.

12. Singer AJ, Arora B, Dagum A, et al. Development and validation of a novel scar evaluation scale. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;120:1892-7.

13. Dart AJ, Dart CM. Suture material: conventional and stimuli responsive. In: Ducheyne P, Healy KE, Hutmacher DW, et al., editors. Comprehensive biomaterials. Elsevier; 2017. p. 746-71.

14. Marturello DM, McFadden MS, Bennett RA, et al. Knot security and tensile strength of suture materials. Vet Surg 2014;43:73-9.