Successful umbilicus salvage following concurrent infraumbilical single-port myomectomy and free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap elevation: a case report

Article information

Abstract

Performing a concurrent gynecologic operation and mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction using a free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap may increase the risk of complications such as umbilical necrosis due to vascular compromise. Imaging studies such as preoperative computed tomography angiography and intraoperative indocyanine green testing can provide information regarding the umbilical blood supply, facilitating decision-making for pedicle selection. Therefore, in situations where a coordinated operation is unavoidable, a thorough preoperative and intraoperative evaluation of the umbilical blood supply is recommended to avoid complications.

INTRODUCTION

The free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap is an effective and widely used method for breast reconstruction. Despite its usefulness, elevation of a free TRAM flap may lead to donor site morbidities such as fat necrosis, abdominal weakness, and seroma collection [1].

Umbilical necrosis is a relatively uncommon complication. A study done by Ricci et al. [2] reported that umbilical necrosis was identified in up to 3.2% of patients who underwent breast reconstruction using abdominal flaps. The umbilicus is an important aesthetic feature of the abdomen [3]. Deformation or absence of the umbilicus is easily noticed and may be an aesthetically devastating problem [4,5]. Furthermore, necrosis of the umbilicus may become a source of infection to the underlying mesh or acellular dermal matrix, which is sometimes used for reinforcement of the flap donor site [6].

Elevation of a free TRAM flap diminishes the blood supply to the umbilicus [7]. Known risk factors that increase the risk of umbilical loss after abdominal-based microsurgical breast reconstruction are smoking [8], high body mass index, a heavier flap, and a thicker abdominal flap [2,9].

Breast cancer patients often present with gynecologic conditions, especially those with BRCA gene mutations. In these patients, a simultaneous gynecologic operation and mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction may sometimes be needed [10]. However, performing a coordinated single operation may increase the risk of flap loss due to vascular compromise and the likelihood of donor site morbidity [11].

Here, we present a case of concurrent single-port myomectomy and immediate breast reconstruction using a free TRAM flap with an infraumbilical incision, wherein pedicle selection was performed based on an evaluation of the blood supply of the umbilicus using preoperative and intraoperative imaging.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old female patient was referred from the department of general surgery for immediate breast reconstruction surgery following mastectomy. The patient was also diagnosed with an 8.7×8.7 cm uterine myoma seen on abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1), which caused severe menorrhagia. The operative plan was established by the gynecology team, who started the operation via a single-port incision, followed by mastectomy performed by the general surgery team and immediate breast reconstruction with a free TRAM flap performed by the plastic surgery team.

Abdominopelvic contrast computed tomography (CT) of a uterine myoma. A massive uterine myoma was noted on and simultaneous excision was recommended by the gynecology team due to increased intra-abdominal pressure.

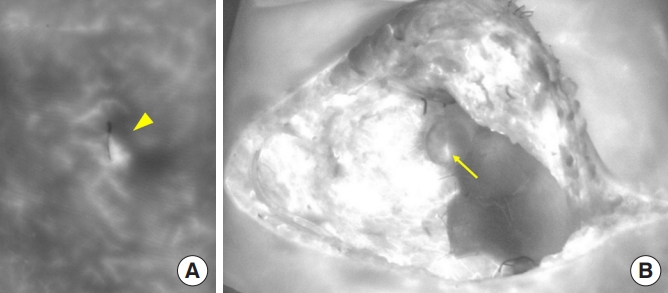

On preoperative abdominal CT angiography, the umbilical blood supply from the right side was seen more clearly than that from the left side (Fig. 2). During the operation, the gynecology team made a single-port incision below the umbilicus, as shown in Fig. 3. Intraoperative indocyanine green (ICG) testing, which is performed as a routine examination at our institution to evaluate mastectomy flap perfusion, was also done in the abdominal area after the gynecologic procedure, just before TRAM flap elevation. The ICG test was carried out using a SPY Portable Handheld Imager (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). The results showed dominant umbilical blood supply from the right side, which aligned with the findings on preoperative angiography CT (Fig. 4). Therefore, to minimize umbilical vascular compromise, we decided to use a free TRAM flap relying on a pedicle from the left deep inferior epigastric vessels. An ICG test was performed once again immediately after flap elevation. Decreased perfusion of the umbilicus was observed, but enhancing areas remained present, especially on the central area and the lower right side of the umbilicus. The blood supply seemed sufficient to prevent umbilical necrosis (Fig. 4). Microanastomosis and flap inset were performed, and donor site closure and neoumbilicoplasty were carried out without any problems. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 6 without any complications, and follow-up visits at 1 and 3 months after surgery did not reveal wound problems in any areas, including the neoumbilicus (Fig. 5).

Preoperative abdominal computed tomography angiography. A dominant perforator arising from the right deep inferior epigastric artery directed towards the umbilicus was noted (yellow arrowhead).

A single-port infraumbilical incision. Photograph of a singleport infraumbilical incision (2.5 cm in length) for uterine myoma excision.

Indocyanine green near-infrared imaging. (A) Diminished perfusion was noted after the gynecologic procedure on the left side of the umbilicus (yellow arrowhead). (B) The vascularity of the umbilicus decreased after elevation of the flap and closure of the fascia defect with acellular dermal matrix, but was still maintained in the center and right portion of the umbilicus (yellow arrow). The previously noted diminished perfusion on the left side of the umbilicus improved slightly after flap elevation.

DISCUSSION

In addition to total mastectomy followed by immediate breast reconstruction, some patients with coexisting gynecologic conditions undergo coordinated operations. Previous studies have discussed the advantages and disadvantages of coordinated single operations compared to sequential operations. Tevis et al. [10] reported that patients who underwent concurrent gynecologic and plastic surgery tended to have higher postoperative complication rates than those who underwent sequential operations. Therefore, in patients without an urgent intra-abdominal issue, an elective operation after the completion of breast surgery was advised to avoid the additional risks posed by concurrent operations.

However, there are unavoidable urgent situations where patients need to undergo coordinated operations. Moreover, increasingly many breast cancer patients also have gynecologic problems and wish to solve both problems in a single operative session under general anesthesia [12]. Coordinated operations are convenient in that they only require patients to undergo the operation and recovery process once. These procedures not only allow early risk reduction for gynecologic cancer development, but also enable early endocrine treatment in cases of hormone-sensitive disease [11]. Despite these advantages, coordinated operations may result in a higher likelihood of umbilical necrosis, especially when incisions compromise the umbilical blood supply.

The umbilicus has been described as the first natural scar of the body, located within the midline at the level of the superior iliac crest [4,5]. The shape and size of the umbilicus vary among individuals, but the umbilicus is essential to the aesthetic appearance of the abdomen. Even minor asymmetries of the umbilicus are easily noticed, and the absence of the umbilicus may be devastating, leading to an unnatural abdominal appearance. Umbilical necrosis represents a rare, yet important aesthetic complication after abdominal-based microsurgical breast reconstruction and once identified, its reconstruction can be extremely challenging.

The umbilicus receives blood supply from the perforators of the deep inferior epigastric arteries, vessels from the ligamentum teres and the medial umbilical ligament and superficially, from the subdermal plexus [7]. This unique structure of the umbilical blood supply needs to be considered, as it is crucial for the viability of the umbilicus in various situations. This was also true in our case, where in addition to free TRAM flap elevation, a gynecologic procedure with the potential to diminish the umbilical blood supply was performed.

Previous attempts have been made to reduce complications relating to the umbilicus using the method of surgical delay [6]. However, this method requires additional surgical procedures at certain time intervals, which undermines the merit of coordinated operations. In cases where a donor site wound complication is suspected, umbilical ablation can also be performed. This also requires a secondary procedure, and the psychological impact of umbilical loss between the operations remains unknown [9].

In our case, we were able to prevent umbilical necrosis by determining the dominant blood supply with the help of preoperative CT angiography and intraoperative ICG testing. The gynecology team was asked to minimize dissection near the umbilicus, especially on the right side, where the dominant umbilical blood supply to the stalk was seen on CT. The intraoperative ICG test performed after the gynecologic procedure once again confirmed umbilical perfusion, allowing us to make an informed decision regarding pedicle selection [13]. As seen in Fig. 4, the right side of the incision showed higher enhancement than the overall dark-colored left side. This meant that the blood supply to the umbilicus was better from the right side and therefore, the left deep inferior epigastric vessels were used as the pedicle for the TRAM flap to preserve the better umbilical blood supply. The ICG test performed again immediately after flap elevation showed decreased perfusion of the overall umbilicus, but still showed stronger areas of enhancement on the right side than on the left. Furthermore, the central area of the umbilical stalk showed strong enhancement, which was thought to be due to the blood supply originating from the ligamentum teres, which is one of the main sources of blood supply for the umbilicus (Fig. 4) [7]. Since gross umbilical congestion was not seen, neoumbilicus formation was performed conventionally, with no requirement for umbilical ablation.

Although our case involved an increased risk of umbilical vascular compromise, we were able to preserve the better source of umbilical blood supply with the help of preoperative CT and intraoperative ICG tests. Therefore, in cases such as coordinated operations where a diminished umbilical blood supply is expected, we recommend thorough examinations both preoperatively and intraoperatively to avoid umbilical necrosis and any further donor site complications.

In conclusion, a simultaneous gynecologic operation and mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction may increase the risk of complications such as umbilical necrosis due to vascular compromise. Preoperative CT angiography and intraoperative ICG tests allowed us to understand the umbilical blood supply, thereby enabling us to make an appropriate decision for pedicle selection. Therefore, in situations where a coordinated operation is unavoidable, thorough preoperative and intraoperative evaluations of the umbilical blood supply are recommended to minimize complications.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-2106-691-701).

Patient consent

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of her images.